The surname Harper has cropped up a number of times in the different family history articles I’ve posted on here. So, I thought it would be appropriate to give the family their own article. It so happens they are connected to a branch of the Stockdale family, who were also cowkeepers in Liverpool. Special thanks are due to John Harper for being so generous in sharing his family's fascinating history.

the harper family

RICHARD HARPER (b.1815) and BETTY CAPSTICK (b. 1819) were farmers near Sedbergh. They had at least ten children: John (b. 1838), Mary (b. 1843), Rosamond (b. 1845), Margaret (b. 1847), Ann (b. 1849), Agnes (b. 1852), Edward (b. 1854), James (b. 1856), Rowland (b. 1858) and Thomas (b. 1861). Three of these children went on to be cowkeepers in Liverpool: John, Rose and Rowland.

JOHN HARPER (1838-1919)

In 1862, John married Dorothy Greenwood (1843-1884) in Sedbergh. The couple had five children, all born in or around Sedbergh: Richard, Elizabeth, Fawcett, Annie and Mary. When Dorothy passed away, in 1884, they were farming at Sunny Side, Frostrow, Sedbergh. By 1890, John had relocated to Liverpool where he was keeping cows at 32 WITHERS STREET. The 1891 census has John at this address with four of his children: Elizabeth, Fawcett, Ann and Mary. John is recorded as living at Withers Street until approximately 1896; by 1900, the dairy was being run by LEONARD MASON. When John died, in 1919, he was living at Toadpool, Frostrow, Sedbergh. His estate was administered by his brothers, James and Rowland (both Farmers).

John’s eldest son, RICHARD HARPER (1862-1942), is also recorded on the 1891 census, but by that time he was married and already living in Liverpool. Richard had married AGNES THWAITE (1867-1960) in 1887, in Sedbergh, and had moved to Liverpool a year later. Richard and Agnes were keeping cows at 53 ANNERLEY STREET. The first six of their nine children were all born in Liverpool, between 1888 and 1898, after which the family returned to farm near Sedbergh.

JOHN HARPER (1838-1919)

In 1862, John married Dorothy Greenwood (1843-1884) in Sedbergh. The couple had five children, all born in or around Sedbergh: Richard, Elizabeth, Fawcett, Annie and Mary. When Dorothy passed away, in 1884, they were farming at Sunny Side, Frostrow, Sedbergh. By 1890, John had relocated to Liverpool where he was keeping cows at 32 WITHERS STREET. The 1891 census has John at this address with four of his children: Elizabeth, Fawcett, Ann and Mary. John is recorded as living at Withers Street until approximately 1896; by 1900, the dairy was being run by LEONARD MASON. When John died, in 1919, he was living at Toadpool, Frostrow, Sedbergh. His estate was administered by his brothers, James and Rowland (both Farmers).

John’s eldest son, RICHARD HARPER (1862-1942), is also recorded on the 1891 census, but by that time he was married and already living in Liverpool. Richard had married AGNES THWAITE (1867-1960) in 1887, in Sedbergh, and had moved to Liverpool a year later. Richard and Agnes were keeping cows at 53 ANNERLEY STREET. The first six of their nine children were all born in Liverpool, between 1888 and 1898, after which the family returned to farm near Sedbergh.

On 22nd March 1893 John’s daughter, ANN HARPER (1872-1925), married EDWARD DINSDALE (1873-1955) at St John’s Church, Fairfield. On the marriage certificate, Edward is recorded as being a Milk Dealer living at 32 Withers Street, but he then set up his own business with Annie, keeping cows at 466 PRESCOT ROAD. For the 1901 and 1911 censuses they were keeping cows at 4 SEACOMBE STREET. When war broke out, in 1914, they returned to live in Yorkshire.

On 21st January 1896, John’s daughter, MARY HARPER (b. 1877), married Sedbergh-born ARTHUR ALLEN (1872-1900). Arthur was the son of cowkeeper SAMUEL ALLEN, of 34 FREEHOLD STREET. They had two children — Samuel Herbert (b. 1897) and Dorothy (b. 1899) — before Arthur died, in 1900. A year later, Mary married William Mason and returned to Sedbergh.

John’s younger son, FAWCETT HARPER (1869-1944) married ISABELLA ELEANOR RAW (1873-1949) in August 1894, at St James’s Church, Liverpool. Isabella was the daughter of ROBERT RAW, who kept cows at 23-25 ROTHWELL STREET (1881), 21 BELMONT ROAD (1891) and 20 TOWN ROW (1901). Fawcett and Isabella had five children: Lily May, Dora Eleanor, Bessie Gladys, John Fawcett and Elizabeth Isabel. Over the years, they kept cows at a number of locations: 102 SMITHDOWN ROAD (1896-98), 104 BERKERLEY STREET (1899-1904) and 52 CHESTNUT GROVE (1905-1929). In 1906, whilst still keeping cows at Berkley Street, Fawcett Harper entered a cow at the Liverpool Cowkeepers’ Association annual show and received a ‘Special Prize awarded by Messrs Lambert and Metcalf’.

FAWCETT HARPER acquired the (by then, award-winning) CHESTNUT GROVE DAIRY in 1905, when his uncle, ROWLAND HARPER (see below) decided to leave the city and return to Sedbergh. The 1911 Census shows just how busy Chestnut Grove Dairy was at that time, requiring a substantial team of operatives to produce, process, sell and deliver the milk taken from up to forty cows kept on the premises: Fawcett Harper (41) Dairy Farmer, b. Sedbergh; Isabella E Harper (38) Assisting in Business, b. Garsdale; Dora Eleanor Harper (15) b. Liverpool; Bessie Gladys Harper (14) b. Liverpool; John Fawcett Harper (10) b. Liverpool; Elizabeth Isabella Harper (5), b. Liverpool; Rachael Fleming (21) Domestic Servant, b. Maghull; Thomas Bousfield (51) Farm Labourer, b. Kirkby Stephen; George Edwards (49) Farm Labourer, b. Shropshire; Leonard Ed. Smith (23) Farm Labourer b. Staffordshire; Thomas Harper (20) Driver, b. Liverpool; and, William Jas. Wilcox (18) Dairy Servant, b. Shropshire. Later that year, the Harper family welcomed a new member to their ranks when Isabella gave birth to a son, Robert Wesley Harper.

The 1928-29 Electoral Register has Fawcett and Isabella still at the Chestnut Grove Dairy, but their ‘Abode’ is given as Dye House Farm, Tarbock, which they had acquired in 1926. They were preparing for retirement, leaving their son, JOHN FAWCETT HARPER (1901-1987) to take over the business at Chestnut Grove. In 1932, John Fawcett married Manx-born Ethel McMaster Elwell (1900-1985) at St Mary’s Church, West Derby, and two years later Ethel gave birth to a son, John Elwell Fawcett Harper. John Fawcett continued the family tradition of winning prizes at the annual show and in 1935 collected a second prize in the class for best ‘Fat Cow, not exceeding 14 cwt.’

The 1928-29 Electoral Register has Fawcett and Isabella still at the Chestnut Grove Dairy, but their ‘Abode’ is given as Dye House Farm, Tarbock, which they had acquired in 1926. They were preparing for retirement, leaving their son, JOHN FAWCETT HARPER (1901-1987) to take over the business at Chestnut Grove. In 1932, John Fawcett married Manx-born Ethel McMaster Elwell (1900-1985) at St Mary’s Church, West Derby, and two years later Ethel gave birth to a son, John Elwell Fawcett Harper. John Fawcett continued the family tradition of winning prizes at the annual show and in 1935 collected a second prize in the class for best ‘Fat Cow, not exceeding 14 cwt.’

When war broke out, many people moved away from the city. Interestingly, an entry in the 1939 Register records John Fawcett and his family on holiday at ‘Towyn’, Twrcelyn, Anglesey: J F Harper, Dairy Farmer, DOB 10th February 1900; E M Harper, Domestic Duties, DOB 13th April 1906; John Elwell Fawcett Harper, at school, DOB 3rd January 1934. The same 1939 Register records Fawcett and Isabella, living in retirement at 11 Smith Drive, having left Dye House Farm the year before following the death of their youngest son, Robert Wesley Harper, due to peritonitis. Then, in 1940, Fawcett and Isabella were living at Holme Lea, Victoria Park, Wavertree. In September 1941, due to the severity of the bombings in Liverpool, John Fawcett sold the Chestnut Grove Dairy to THOMAS ELLIS and evacuated his family to his wife’s place of origin, the Isle of Man. Fawcett and Isabella followed their son and his family to the Isle of Man, and both died there: Fawcett in 1944 and Isabella in 1949. At the time of their respective deaths, they were living in Castletown, but both were subsequently buried at Holy Trinity Church, Wavertree.

John Fawcett and his family next appear on the Liverpool Electoral Register in 1959, when they were living at Bower Cottage, ROSE LANE; the cottage attached to Bower Bank, which was the dairy owned by EDWARD HARPER (the cousin of Fawcett Harper). Although their home was in the Isle of Man, the family began 'wintering' in Liverpool, as their two children were now in further education on the mainland. By 1962, the family had moved round the corner and were living at 15 Rose Brae. The family were still at the Rose Brae address for their last appearance on the Liverpool Electoral Register in 1969-70. This coincides with John Ewell Fawcett Harper's move in 1968, back to the Isle of Man, where he and his wife, Patsy, founded the Shebeg Pottery company.

ROSAMOND [Rose] HARPER (1845-1898)

Rosamond married WILLIAM HENRY ELLIS (1838-1894) in October 1868, in Sedbergh. They had eight sons before they moved to Liverpool. In 1891 they were keeping cows at 104 BERKERLEY STREET, assisted by their sons, Henry (20) and Richard (19) and also by Rose’s daughter, Elizabeth Harper (24). William passed away not long after that, in April 1894, and the dairy was eventually taken over by Rosamond’s nephew, FAWCETT HARPER (1901).

ROWLAND HARPER (1858-1924)

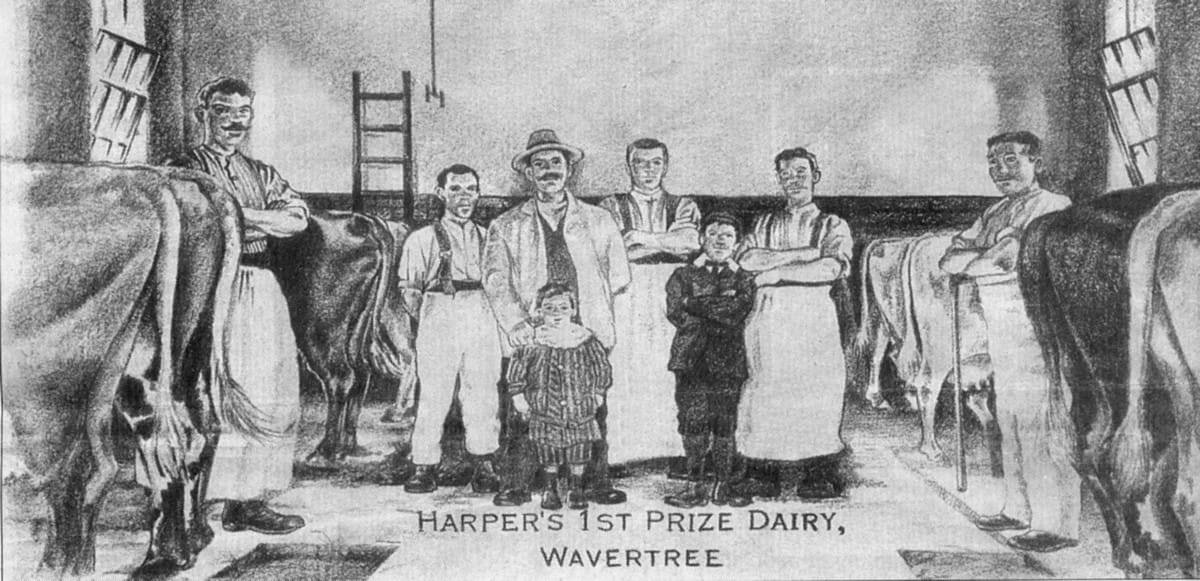

Rowland Harper married SARAH JANE MASON (1867-1937) in 1887, in Sedbergh. Between 1891 and 1910 they had eight children, all born in Liverpool. In 1891 the family were living at 61a HIGH STREET, Wavertree. There was enough land at this location for Rowland to call himself a ‘Farmer’. However, by 1897 (Electoral Register) they had moved round the corner to 52 CHESTNUT GROVE and his occupation was then given as ‘Cowkeeper’. In 1899, Rowland achieved considerable success in local shows. At the annual show organised by the Liverpool and District Cowkeepers’ Association he won a first prize for a ‘Fat Cow, not exceeding 13 cwt.’ and a second prize for a ‘Fat Cow, 14½ cwt. and upwards’. But his biggest success came in the Lancashire County Show, being held in Liverpool that year, when he was awarded First Prize Gold Medal (and £10 prize money) for the ‘Best Kept Shippon, Milkhouse, and Shop or Dairy in Liverpool or Bootle’. He celebrated this success by erecting a huge hoarding above the gates to the yard.

By the sheer number of people living and working there, the 1901 Census gives an idea of the scale of operation at Chestnut Grove: Rowland Harper (42) Cowkeeper, b. Sedbergh; Sarah J Harper (34) b. Sedbergh; Elizabeth Harper (10) b. Wavertree, Liverpool; Richard Harper (8) b. Wavertree, Liverpool; Thomas Harper (5) b. Wavertree, Liverpool; Edward Harper (1) b. Wavertree, Liverpool; Thomas Mason (75) Retired Farmer, (Father-in-Law), b. Killington, Westmorland; George Ellis (22) Dairy Hand, b. Oxenholme, Westmorland; Sam Coupland (19) Dairy Hand, b. Witherslack, Westmorland; James Chesters (17) Dairy Hand, b. Bradley, Cheshire; Jane Richardson (18) Domestic Servant, b. Sedbergh; Betsy Handley (25) Domestic Servant, b. Sedbergh. This record also reflects the practice of city dairies recruiting workers from the home parish and/or from the extended family.

The 'Prize-winning Dairy' hoarding was still in place in 1905, when the Chestnut Grove Dairy was handed on to Rowland’s nephew, FAWCETT HARPER. Rowland, Sarah and their children returned to Sedbergh to farm at Dove Cote Gyll, Dowbiggin (1911 census).

Rowland Harper married SARAH JANE MASON (1867-1937) in 1887, in Sedbergh. Between 1891 and 1910 they had eight children, all born in Liverpool. In 1891 the family were living at 61a HIGH STREET, Wavertree. There was enough land at this location for Rowland to call himself a ‘Farmer’. However, by 1897 (Electoral Register) they had moved round the corner to 52 CHESTNUT GROVE and his occupation was then given as ‘Cowkeeper’. In 1899, Rowland achieved considerable success in local shows. At the annual show organised by the Liverpool and District Cowkeepers’ Association he won a first prize for a ‘Fat Cow, not exceeding 13 cwt.’ and a second prize for a ‘Fat Cow, 14½ cwt. and upwards’. But his biggest success came in the Lancashire County Show, being held in Liverpool that year, when he was awarded First Prize Gold Medal (and £10 prize money) for the ‘Best Kept Shippon, Milkhouse, and Shop or Dairy in Liverpool or Bootle’. He celebrated this success by erecting a huge hoarding above the gates to the yard.

By the sheer number of people living and working there, the 1901 Census gives an idea of the scale of operation at Chestnut Grove: Rowland Harper (42) Cowkeeper, b. Sedbergh; Sarah J Harper (34) b. Sedbergh; Elizabeth Harper (10) b. Wavertree, Liverpool; Richard Harper (8) b. Wavertree, Liverpool; Thomas Harper (5) b. Wavertree, Liverpool; Edward Harper (1) b. Wavertree, Liverpool; Thomas Mason (75) Retired Farmer, (Father-in-Law), b. Killington, Westmorland; George Ellis (22) Dairy Hand, b. Oxenholme, Westmorland; Sam Coupland (19) Dairy Hand, b. Witherslack, Westmorland; James Chesters (17) Dairy Hand, b. Bradley, Cheshire; Jane Richardson (18) Domestic Servant, b. Sedbergh; Betsy Handley (25) Domestic Servant, b. Sedbergh. This record also reflects the practice of city dairies recruiting workers from the home parish and/or from the extended family.

The 'Prize-winning Dairy' hoarding was still in place in 1905, when the Chestnut Grove Dairy was handed on to Rowland’s nephew, FAWCETT HARPER. Rowland, Sarah and their children returned to Sedbergh to farm at Dove Cote Gyll, Dowbiggin (1911 census).

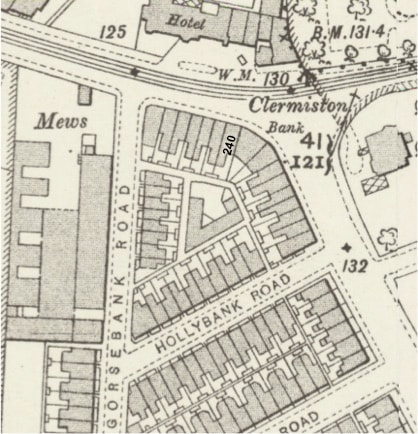

In 1924, the youngest of Rowland’s three sons, EDWARD HARPER (1899-1986), married DORIS STOCKDALE (1898-1978) in Sedbergh. Doris was the daughter of cowkeeper THOMAS STOCKDALE, and had been born in Liverpool. In 1935 Edward and Doris returned to Liverpool and Edward took over a purpose-built cowhouse and milkhouse, MOSSLEY HILL DAIRY, in ROSE LANE, which he bought from ROBERT WILSON. The semi-detached premises at Rose Lane incorporated a main house, Bower Bank, for the cowkeeper’s family, and a 2-up-2-down cottage designed to house an employee — a cowman — and his family. For a while this cottage was occupied by JOE CAPSTICK, until 1944 when he relocated to run his own dairy at 4 MARLBOROUGH ROAD in Tuebrook. Later, it was occupied by Fawcett Harper and his family. To the side of the house, in Rose Brae, was a doorway into the dairy shop and further down the side street was a gated yard with a shippon, stable, hayloft, midden and cart shed. Mossley Hill Dairy, also known as Harper’s Dairy, is one of the best preserved cowkeeping dairies in Liverpool, combining both cowhouse and milkhouse as an integrated property.

In 1936, Edward enjoyed considerable success at the Liverpool and District Livestock Society’s annual show, taking first prize in both the class for best ‘Cow, not exceeding 12cwt.’ and the class for best ‘Cow in calf or milk (UK)’. He was also awarded the Metcalfe Challenge Shield. Two years later, in 1938, he entered a roan cow at the Lancashire County Show at Liverpool and received a ‘Highly Commended’ in the class for best ‘Dairy cow in calf, any weight, to calve within 3 months after the show’.

Edward and Doris had three children — Margaret (b. 1925), Thomas Rowland (b. 1928) and Joan (b. 1932) — but it was the youngest, Joan, who would carry on the family business. In 1954, she married James R Fenney, at All Hallows Church, Allerton. The couple moved in with Edward and Doris at Bower Bank. Edward kept cows there until 1954. Doris died in 1978 and Edward in 1986, but Joan and James continued to deliver milk right up until the late 1990s.

In 1936, Edward enjoyed considerable success at the Liverpool and District Livestock Society’s annual show, taking first prize in both the class for best ‘Cow, not exceeding 12cwt.’ and the class for best ‘Cow in calf or milk (UK)’. He was also awarded the Metcalfe Challenge Shield. Two years later, in 1938, he entered a roan cow at the Lancashire County Show at Liverpool and received a ‘Highly Commended’ in the class for best ‘Dairy cow in calf, any weight, to calve within 3 months after the show’.

Edward and Doris had three children — Margaret (b. 1925), Thomas Rowland (b. 1928) and Joan (b. 1932) — but it was the youngest, Joan, who would carry on the family business. In 1954, she married James R Fenney, at All Hallows Church, Allerton. The couple moved in with Edward and Doris at Bower Bank. Edward kept cows there until 1954. Doris died in 1978 and Edward in 1986, but Joan and James continued to deliver milk right up until the late 1990s.

In an article published online by the BBC on 12th September 2011 (www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-merseyside-14855763), Joan describes the demise of the family’s dairy in Rose Lane, Mossley Hill:

Joan Fenney, 79, who has lived in the dairy on Rose Lane since she was three-years-old, said it was a close-knit family business.

"We took over the milk business in 1935 and my mother and father worked it," she said. "We had 30 cows, two horses and one bull and I started working the milk round when I was 16, delivering and collecting.

My aunt was at Allerton Farm Dairy, my grandfather had the place at Chestnut Grove in Wavertree, and my mother's family had the place opposite the Brookhouse pub on Smithdown Road."

The dairy was very much part of home life and the shop was a room in the house so the family was always on hand to serve customers. The white tiled room still remains, complete with black and white counter, but the shelves are now lined with empty egg boxes and plants. Outside, the shippon, where the cows were kept, still stands with the original feeding troughs, the stall for the horse and even the old milk crates still stacked in the corner.

"The cows went in the early 1950s but we carried on selling through the shop," Mrs Fenney continued. "The business was changing."

As big corporate dairies began to take over, the smaller ones began to close. Local dairies tried to survive by buying in milk to continue to deliver on their rounds. Harper's managed to keep the dairy shop running by buying in milk to sell but finally closed in 2000, something which Mrs Fenney says was due to a rise in local supermarkets.

"It was so upsetting, it just fell through your fingers," she said. "As soon as they built the supermarkets people said 'No, we won't leave you', but they did. You dreaded getting a note in the bottle saying 'No milk till further notice'. You knew very well that they wouldn't start again."

Joan Fenney, 79, who has lived in the dairy on Rose Lane since she was three-years-old, said it was a close-knit family business.

"We took over the milk business in 1935 and my mother and father worked it," she said. "We had 30 cows, two horses and one bull and I started working the milk round when I was 16, delivering and collecting.

My aunt was at Allerton Farm Dairy, my grandfather had the place at Chestnut Grove in Wavertree, and my mother's family had the place opposite the Brookhouse pub on Smithdown Road."

The dairy was very much part of home life and the shop was a room in the house so the family was always on hand to serve customers. The white tiled room still remains, complete with black and white counter, but the shelves are now lined with empty egg boxes and plants. Outside, the shippon, where the cows were kept, still stands with the original feeding troughs, the stall for the horse and even the old milk crates still stacked in the corner.

"The cows went in the early 1950s but we carried on selling through the shop," Mrs Fenney continued. "The business was changing."

As big corporate dairies began to take over, the smaller ones began to close. Local dairies tried to survive by buying in milk to continue to deliver on their rounds. Harper's managed to keep the dairy shop running by buying in milk to sell but finally closed in 2000, something which Mrs Fenney says was due to a rise in local supermarkets.

"It was so upsetting, it just fell through your fingers," she said. "As soon as they built the supermarkets people said 'No, we won't leave you', but they did. You dreaded getting a note in the bottle saying 'No milk till further notice'. You knew very well that they wouldn't start again."

LIFE AT CHESTNUT GROVE DAIRY

The dairy at Chestnut Grove was handed down through several generations of the Harper family, beginning in 1897 with Rowland Harper, who then passed it on to his nephew, Fawcett Harper in 1905. Fawcett passed it on to his son, John Fawcett Harper in 1932, who continued the business until the bombings of 1941 forced him and his family to sell up and leave the city. Included in that family of evacuees was seven-year-old John Elwell Fawcett Harper, who some sixty years later recalled his childhood at Chestnut Grove in an article published in Farmers Weekly on 13th April 2001:

‘Age of Town Dairying Recalled.’ By John Harper.

In the early 1900s there were 4000 dairy cows within the Liverpool city boundary. They were kept, usually about 40 at a time, in premises that had been purpose built, probably in the middle to late 1800s, to supply the growing town population with fresh milk.

In 1932 my father became the third generation owner/occupier of one of those town milkhouses at 52 Chestnut Grove, Wavertree, Liverpool. The buildings are still there but not used now for their original purpose. All the milkhouses were made up of the same elements but they varied a little in layout. Often they stood on the corner of two streets,

At Chestnut Grove the rectangular cobbled yard had house, stables and some looseboxes on one of the long sides, and shippon for 38 cows, with hay loft above, on the other. The inner short side, furthest from the street, was roofed over from the stable almost to the shippon to make an open-fronted shelter for two horse-drawn milk floats.

Under the gap in this roof alongside the shippon there was, built against the shippon wall, a brick and cement midden container like a small, deep swimming pool. Hand labour with a fork and wheelbarrow filled it and it was emptied weekly with a fork into a lorry to be carted away to farm land.

At my father’s place he built with big slate slabs against the stable wall, another similar container for brewers’ grains. These with molasses made an important part of the cows’ rations. Cattle cake and some of the winter hay was bought in, but summer grass came from Liverpool’s golf courses and parks. Some of that father made into hay. Everything went in or out through the big door which rolled sideways to open onto the street at the other short side of the yard.

My father took over from his father in 1932 when he and my mother married. She had no farming background and had been at the time of her marriage a ladies fashion buyer in one of the big city centre stores. In one drastic move she was out of that world and bottling milk with a hand measure from the churns at 5 o’clock in the morning in the yard in the chill of winter. Or in the shippon in the evening, when the men had gone home or out, holding a cow by the horns while her husband drenched it with a patent, Vitalis, Cataline or one of the Day and Sons’ impressively coloured fluids.

There were some ‘wonderful’ home remedies: for a cold, an onion and lard would be pushed into a slit made in the cows brisket; a chill in the udder was treated with hot cow muck taken as it dropped and plastered by hand onto the udder. I must have been less than seven years old (and pretty surprised, because I remember it still) when I saw that treatment used. No one had a lot of faith in the vets in the 30s, they had no antibiotics and so, though their diagnoses would be accurate, their remedies were uncertain.

The dairy at Chestnut Grove was handed down through several generations of the Harper family, beginning in 1897 with Rowland Harper, who then passed it on to his nephew, Fawcett Harper in 1905. Fawcett passed it on to his son, John Fawcett Harper in 1932, who continued the business until the bombings of 1941 forced him and his family to sell up and leave the city. Included in that family of evacuees was seven-year-old John Elwell Fawcett Harper, who some sixty years later recalled his childhood at Chestnut Grove in an article published in Farmers Weekly on 13th April 2001:

‘Age of Town Dairying Recalled.’ By John Harper.

In the early 1900s there were 4000 dairy cows within the Liverpool city boundary. They were kept, usually about 40 at a time, in premises that had been purpose built, probably in the middle to late 1800s, to supply the growing town population with fresh milk.

In 1932 my father became the third generation owner/occupier of one of those town milkhouses at 52 Chestnut Grove, Wavertree, Liverpool. The buildings are still there but not used now for their original purpose. All the milkhouses were made up of the same elements but they varied a little in layout. Often they stood on the corner of two streets,

At Chestnut Grove the rectangular cobbled yard had house, stables and some looseboxes on one of the long sides, and shippon for 38 cows, with hay loft above, on the other. The inner short side, furthest from the street, was roofed over from the stable almost to the shippon to make an open-fronted shelter for two horse-drawn milk floats.

Under the gap in this roof alongside the shippon there was, built against the shippon wall, a brick and cement midden container like a small, deep swimming pool. Hand labour with a fork and wheelbarrow filled it and it was emptied weekly with a fork into a lorry to be carted away to farm land.

At my father’s place he built with big slate slabs against the stable wall, another similar container for brewers’ grains. These with molasses made an important part of the cows’ rations. Cattle cake and some of the winter hay was bought in, but summer grass came from Liverpool’s golf courses and parks. Some of that father made into hay. Everything went in or out through the big door which rolled sideways to open onto the street at the other short side of the yard.

My father took over from his father in 1932 when he and my mother married. She had no farming background and had been at the time of her marriage a ladies fashion buyer in one of the big city centre stores. In one drastic move she was out of that world and bottling milk with a hand measure from the churns at 5 o’clock in the morning in the yard in the chill of winter. Or in the shippon in the evening, when the men had gone home or out, holding a cow by the horns while her husband drenched it with a patent, Vitalis, Cataline or one of the Day and Sons’ impressively coloured fluids.

There were some ‘wonderful’ home remedies: for a cold, an onion and lard would be pushed into a slit made in the cows brisket; a chill in the udder was treated with hot cow muck taken as it dropped and plastered by hand onto the udder. I must have been less than seven years old (and pretty surprised, because I remember it still) when I saw that treatment used. No one had a lot of faith in the vets in the 30s, they had no antibiotics and so, though their diagnoses would be accurate, their remedies were uncertain.

A comparatively large workforce was needed. Two men and my mother’s housemaid lived in and there were two married men, Ted Sixsmith and Jim Airey, who lived nearby. Mother, thrown in at the deep end again, catered for this staff and some part-timers — anyone who could hand-milk or would help to bottle it. Boys about 13-years-old, in their last year at school, came early in the morning to deliver milk to customers nearby. They loaded carrier bikes with several metal crates full of bottles and wriggled off balancing this heavy load even across the tram line junctions on Wavertree Road. Father and Jim Airey delivered by horse-drawn float twice a day to doorsteps further away.

Milking in the hot shippon made a lot of sweat even though it was quite a cow palace for those days, being high ceilinged with big windows and tiled with glazed brown tiles up to shoulder height. In 1899 it had been awarded the Lancashire Agricultural Society’s Gold Medal. Cows stood in pairs in wooden partitioned stalls, heads facing the two long walls with a wide passageway through the middle of the shippon.

Cleanliness was routine, with sawdust bedding fresh daily on the concrete floor (not much cow comfort). One of the signs of trouble that needed to be listened for was the characteristic soft cough of the animal with pulmonary tuberculosis. TB was still a human plague in those days. It was more comfortable to milk wearing only singlet and trousers and winter colds were easily caught by the sweating milkers when they took their full buckets to the cooler-room in the outside chill.

There were “plenty of problems in the milk job in them days,” father said. When the Co-operative Wholesale Society tried out doorstep deliveries it began to campaign to pinch customers from the cowkeepers. So it happened that father found free samples of Co-op milk on some of his clients’ doorsteps. He did not lose any customers to the Co-op. He made sure of that but always asked, “How did you like the Co-op milk missus?” The replies did not vary much; they ran along the lines of, “Don’t talk to me about Co-op milk!” “Oh dear,” he would sympathise. “What was up with it?” He knew well enough what was up with it, because his solution to the problem had been to collect up the sample bottles on the day he found them, put them in the oven of the kitchen range overnight and return them to the doorsteps nicely soured the morning after.

The cows came in freshly calved, mostly from Preston Auction where father bought them himself. They stayed in their stalls and never went out until their daily yield fell below 3 gallons. Some would go to the butcher, some would be sold onto dealers such as Rabinowitz or ‘Cock’ Parry to calve elsewhere to the Dairy Shorthorn bull that was kept. ‘Cock’ Parry was a small lame man who always wore highly polished brown boots and leggings. He “needed watchin’!” father said. Rabinowitz or Rab as everyone called him was a Russian Jew, well known as a fair dealer and still remembered by the oldest throughout the north. Rab came to England in his teens on a cattleboat and never went back. He told father that he took his first cow to market for his father, and sold it, when he was nine-years-old.

The float horses were vanners, mostly from Crewe or North Wales. Now and then from Jack Low, the blacksmith and coal merchant who operated from an alley not far away near Picton Clock. Jack often made a social call at about 11am when father came in from his early milk round and would be eating breakfast-cum-lunch. Jack had a leaning place where he blackened the wall paper with his unwashed clothes; he had no wife. He knew well that there were no passengers tolerated in father’s economy. So when mother bought a goldfish for my sister and me, Jack was sarcastic. “God, a non-producer at last,” he observed.

By 1940 when the war was properly under way the government began rewarding the cowkeepers with a subsidy on each gallon produced. Consternation set in because this was a complete about-turn. Previously a small levy had been put on each gallon by the MMB to pay for its activities when it started up in 1933. In spite of the service the board had given the cowkeepers in fixing a fair price for milk, which they all regarded as a godsend, they had all written down their daily production as far as they dared to avoid the levy. Now the changed system left them stranded, unable to reveal their true output to claim the full subsidy.

Then came the hard winter of 1940-41 with snow-bound streets. Most of the cowkeepers had gone over to delivery by motor-vans. Not at our place though and our daily gallonage was banged up to about double straight away. Of course an inspector came round as soon as our claim landed on his desk. “Them vans can’t cope with the cold and ice but my horses can,” father told him. “And I’ve got more customers now than I can serve. Housewives are stoppin’ me in the street. I’ve had to buy more cows.” All true that. It’s an ill wind.

By the 1920s the heyday of the Liverpool cowkeepers had already passed. Now refrigerated transport fetched milk from far afield. Big dairy companies such as Hansons began buying rounds from men who wanted to retire. The cowkeepers usually went back to the Yorkshire and Cumbria Dales, particularly to the Sedbergh area from where their ancestors had come and where they had kept their links. A few like John Winn in Smithdown Road carried on well into the 1950s. My Harper cousin in Rose Lane, Mossley Hill, stayed and put in battery hens where the cows had been. He bought milk wholesale from United Dairies for retailing to his customers. The last to have cows were the Capsticks in Tuebrook. They gave up in 1975.

It was the Second World War that put an end to my parents’ time in the business. Specifically it was the bombing blitz by the Luftwaffe in 1941 that changed our lives. Under the house was a dairy shop with a way in down steps from the street and also from the yard and from the house kitchen. When the air-raids began father brought in railway sleepers and pit props to brace the shop ceiling. My parents had a double bed behind the counter, my sister and I slept on the slate slab shelves against the walls. She and I heard the bombing of the docks 2 miles away but we were too young to be frightened. Neither that nor the buzz and rattle of the fridge motor in the next room with the bottle-washing plant (hot water, soda and motorised brushes in a tank) kept us children awake.

I remember the clatter of the live-in men’s boots as they raced down from the street where they had been watching the searchlights, the anti-aircraft fire and the flashes of the bombs exploding on the docks. They ran in when the bombs began tracking towards us.

It was when my mother’s widowed father, in his room on the first floor, saw incendiaries straddle the premises that our move was decided on. That and the heaps of rubble father saw on his rounds where houses had been the day before. We were not going back to the Ghyll, the farm near Sedbergh where our branch of the Harpers hailed from, but to the Isle of Man, land of my mother’s birth.

On one of his last calls, Jack Low, leaning on the wallpaper and smelling acridly of burnt horn, was asked if he would be coming to see us there. “I’m afraid of the water,” he said. The mark on the wall gave Annie, my mother’s housemaid, extra work; it annoyed her no end. “Tell us something we didn’t know,” said she.

The Stockdale family

The Stockdales are related to the Harpers through the marriage of EDWARD HARPER (1899-1986) and DORIS STOCKDALE (1898-1978). Doris was the youngest child of THOMAS STOCKDALE (1865-1921) and Margaret Handley (1862-1927), who were married at Sedbergh in 1885. As well as Doris (b. 1898, Liverpool), their other children were: Ethel (b. 1887, Sedbergh), Maud (b. 1891, Liverpool) and Robert James (b. 1896, Liverpool). The 1891 census records the newly-arrived family in Liverpool, at 40 LARCH LEA. Thomas’s occupation is given as Cowkeeper and he is living with his wife and their first three children. In 1895, the family moved their business to 2-4 TOWNSEND LANE, known as ANFIELD DAIRY. It is likely that Thomas acquired this property from cowkeeper EDMUND FOSTER, who had also come to Liverpool from Sedbergh. At this property, in 1896, Doris gave birth to Robert James, the youngest of their four children.

By 1900 (directory), the family had moved to 240 SMITHDOWN ROAD. This property was a shop in a prominent high street location on the corner of Smithdown Road and Greenbank Road. Unusually for a cowkeeping dairy, it was a mid-terrace rather than an end-terrace property, but to the rear of the block of shops was a separate property consisting of a yard and outbuildings. This second property was where Thomas kept his cows, and some of these were prize-winners at the annual show organised by the Liverpool & District Cowkeepers’ Association:

1905 — Best Fat Cow, not exceeding 11½ cwts. 3rd. T. Stockdale.

1906 — Best Fat Cow not exceeding 11½ cwts. 1st. T. Stockdale, Smithdown Road.

Best Fat Cow not exceeding 14½ cwts. 2nd. T. Stockdale, Smithdown Road.

In 1908, their daughter, ETHEL STOCKDALE, married THOMAS EDWARD HERD (1876-1947) at St Matthew & St James Church, Mossley Hill. They opened a dairy and began keeping cows at 7 NEWTON STREET (1911). They had five children: Doris (1909-1978), Margaret (b. 1911), Thomas Edmund (1912-1997), Norman (1915-1959) and Maud (1917-1918). Thomas and Ethel were still living at Newton Street in 1934/5, but by 1938 they had moved to ALLERTON FARM, Allerton Road. Following their deaths— Thomas Edward in 1947 and Ethel in 1954 (address given as 163 Allerton Road) — the business passed to their son, NORMAN HERD.

Thomas and Margaret stayed at the 240 SMITHDOWN ROAD dairy until about 1919, when they returned to Sedbergh. When Thomas died, on 23rd August 1921, he was living at Bank Cottage, Frostrow, Sedbergh. His wife, Margaret, died six years later. After marrying Rosa Bainbridge in 1923, their son, Robert James, became a Dairy Farmer at Bank Cottage Farm, Sedbergh (1939 Register).