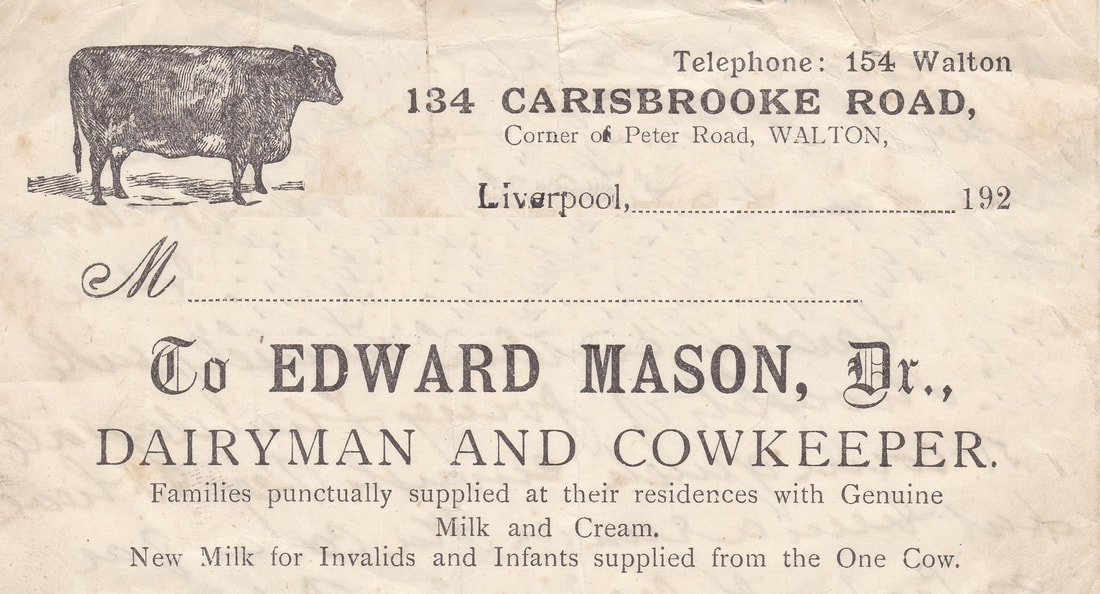

I was delighted to receive from Robert Mason, the memoirs of his grandfather, Edward Ewbank Mason, written in the late 1980s. Although Edward spent all of his working life in the insurance industry, his childhood and adolescent years were spent living and working at the family’s dairy at 134 Carisbrooke Road, Walton, Liverpool. This property is more commonly associated with the Bargh family - probably due to the widespread circulation of a photograph of George Bargh and his prize-winning cow, taken outside 134 Carisbrooke Road. George Bargh and Edward Mason were cousins. However, Edward’s memoirs predate George’s involvement and provide a detailed description of the property, its origins and what life was like for the son of a city cowkeeper in the early 1900s.

To give some context to the memoirs, I’ve put together a short genealogy of the Mason family as it relates to Edward Ewbank Mason (1909-1991).

The Paternal Line:

Edward Mason (1831-1908) married Hannah Bargh (1831-1873) in January 1863. They farmed 170 acres near Wray and had two sons: George (b.1870) and Edward (1872-1934). Sadly, Hannah died prematurely, in 1873. Edward remarried and in 1877 was joined in wedlock to Harriet Saltimer (1843-1926).

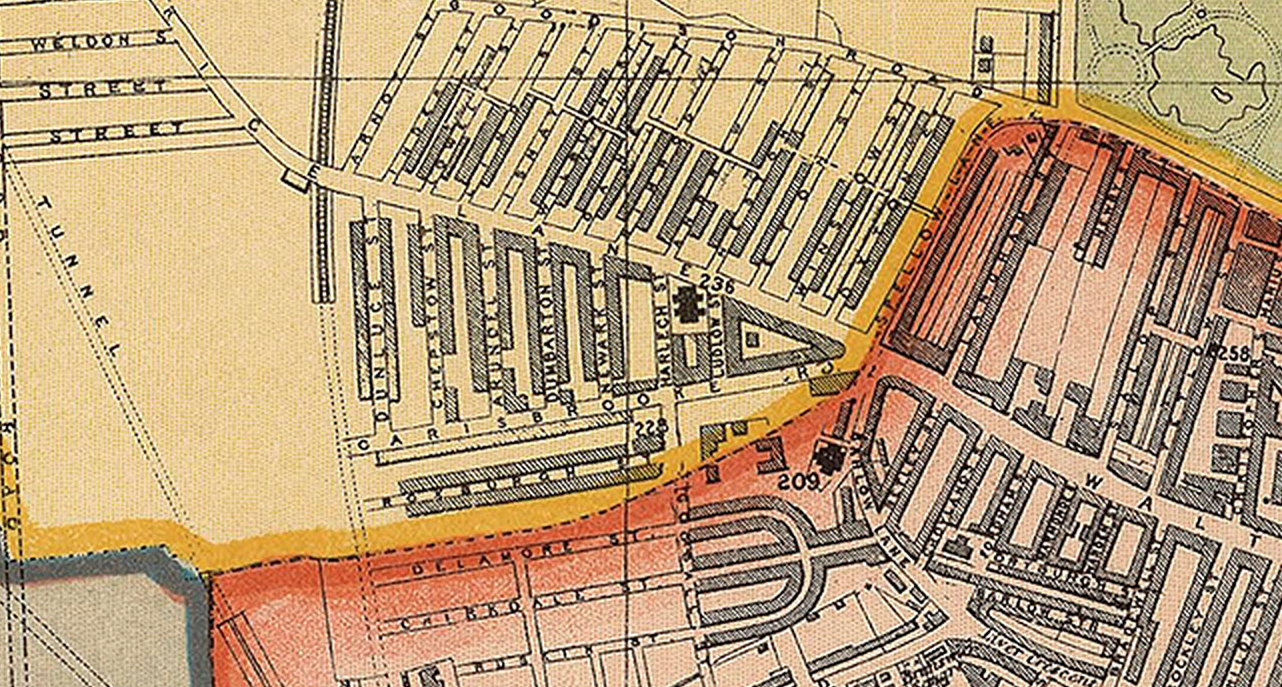

Although he was still farming at the time of the 1881 census, ten years later the family had relocated to Liverpool and were keeping cows at 88 Carisbrooke Road, Walton. Subsequently, they built a more spacious dairy on land further up Carisbrooke Road - this property would become 134 Carisbrooke Road.

The elder son, George, left home when he married Esther Houghton in 1894 and went on to keep cows at 31-33 Guildhall Road, Aintree (1901) and 42-44 Trevor Road, off Orrell Lane (1911, 1938). In 1924 he won a prize for the best heavyweight cow at the annual cattle show in Liverpool. The younger son, Edward, married Mary Ewbank in 1899. He continued running the dairy at Carisbrooke Road after his father passed away in 1908.

The Maternal Line:

Christopher Falshaw Ewbank (1845-1883) married Mary Metcalfe Pratt (b.1844) in Askrigg in 1863. In 1871 they were farming at Walden Head, Burton-with-Walden, North Yorkshire. By 1881 they had relocated to Liverpool and were keeping cows at 15 Barlow Lane, Walton – not far from Carisbrooke Road. At the time, they had six children living with them: Thomas (age 12), Mary (age 9), James (age 6), Margaret (age 6), Isabella (age 5) and John (age 1). Although Christopher died just two years later, the family remained in Liverpool and their eldest daughter, Mary, married Edward Mason in 1899.

So, Edward Mason and Mary Ewbank were married on 8th June 1899, in Liverpool. In 1901 they and their daughter, Hannah (1 year), were living with Edward's parents at 134 Carisbrooke Road. The 1911 census records them still living at 134 Carisbrooke Road, but now with four children: Hannah (age 11), Ethel Mary (age 9), Margaret [Peg] (age 6) and a very young Edward [Ewbank] (age 1). This sets the scene for Edward Ewbank Mason’s memoirs.

Extracts from the Memoirs of Edward Ewbank Mason (1909-1991)

Introduction

“My father, Edward Mason, was born outside Lancaster. He had one brother, George Mason. They farmed at a little village called Wray, near Hornby. I doubt if they could be regarded as successful farmers in as much as sometime in the late 1880s or possible 1890 grandfather Mason decided to leave Wray with his two sons and to move to Liverpool and to start a dairy. Initially they opened up in quite a modest way at a dairy at the corner of Chepstow Street and Carisbrooke Road in Walton, Liverpool. It was a small place, but satisfied with their endeavours to date, grandfather Mason and his two sons, decided on a very bold move. About the turn of the century, they got down to planning a purpose-built dairy and cowshed.

When they built Carisbrooke they expected the new housing to continue to develop. But it didn’t. Building ceased, and instead of being surrounded by houses we were literally ‘out on a limb’. And this lack of potential development would have a disastrous effect on the fortunes of the dairy.

Uncle George did not figure too prominently in this move. He got married and opened out in his own dairy at Aintree, Liverpool. And to all extent passed off the scene of the new venture. My father, grandfather and the latter’s second wife, settled in at Carisbrooke Road. And my mother, a young bride, would join them at the start of her married life. Not a happy beginning, I suggest for a married couple to start their joint life.”

Edward Ewbank Mason - age 8

© Robert Mason 2018

Edward Ewbank Mason - age 8

© Robert Mason 2018

Carisbrooke Dairy

“I think the construction of the new dairy at 134 Carisbrooke Road, Walton, Liverpool, needs some description. Not only for its grandiose construction (of those days), but because of the trade carried on. A trade long since ended.

First, the buildings. The main rooms on the ground floor - back kitchen, kitchen, dairy, and parlour – were all fair sized rooms. The back kitchen was where the meals were prepared. The kitchen was the centre of the world of ‘Carisbrooke’. The parlour was only used on festive occasions. And the dairy? Well, a certain amount of trade was done there, but not so very much, as we ‘went to the customer’, rather than vice versa. We had five bedrooms and commodious cellar, attic and hallway.

Perhaps more important and more of interest would be my description of the outbuildings — cowshed, stables, washhouse. Yes, we had a large washhouse, which was used for domestic purposes. Stables. Well, we had three horses, and adequately and well housed were these animals. Now, the cowshed (I wish I could use a more polite descriptive word, but I can’t. Cowshed it was to me in my youth, and cowshed it is now in old age). Shippon perhaps sounds better. Anyway in the shippon we had stalls for 32 cows. Our boast, I suppose, was that we sold milk straight from the cow to the customer. And on the yard between the shippon and the house we had a large brick-built midden to collect the manure from the cows. And in the yard, too, we kept the milk floats, two of them.

The midden or manure pit was not too oppressive a sight. It was emptied possibly twice a week by farmers from farms on the outskirts of Liverpool - potato and crop farmers, who would make an eight- to ten-mile journey each way to collect the manure. They used their own wagons for this purpose. One man, the driver, and our cowman would help load his wagon. Loads of three to five tons of manure each journey. And from memory, I sometimes made up the manure accounts. We got fifteen shillings a ton.

Above the cow stalls/stables a loft ran the whole length of the building. And we spent many happy hours playing amongst the baled hay — to the annoyance of Father who strongly and sometimes painfully expressed his annoyance at our noise upsetting his beloved cows.

So much for the bricks and mortar. Let me try and put some bones on this brief descriptive picture of Carisbrooke. Animals first. Every week — it seemed — Father would go off for the day to Preston Cattle Market. Sometimes he bought for himself, sometimes for other milkmen presumably on a commission basis. Sometimes he just went for the day out. Yes, Father liked his day off. Equally, whatever else, he was a very good judge of cattle and a good stock handler. In all my years at Carisbrooke I’ve no clear recollection of a ‘Vet’ coming near the premises. Father dosed and treated the cattle himself. He knew his job.

I got an early apprenticeship to the cattle trade. I think I must have been a little lad of seven, possibly eight years old, when Father awoke me about 5.00 am. I would think, initially, to go with him as company, but later to play a major part. The cows bought at Preston would be loaded into railway trucks on a Friday afternoon, travel to Liverpool and remain in the railway trucks overnight until we collected them on Saturday morning. Usually five/six cows, frightened out of their wits by the train noise and the other hideous noises of a city. Yes, when they were first let loose they just ran wild — madly. I was at the front, instructed to turn them, not let than get away. And armed only with a stick it took real courage to stand in front of five madly charging beasts. And when you had managed to get them in some order you could quickly find yourself trying to stop yet another stampede caused by that horrible clanging of a tram or steam-lorry passing by. It was to be many years before delivery by vehicles direct from market to purchaser was to ease my lot. But I learnt in a hard school. I don’t know which I feared most — a buffet in the ribs from a charging beast or Father’s quite vitriolic comments if I let one of his cows get away.

The cows at Carisbrooke were well housed and regularly fed. Their diet was good quality hay and ‘tubs’ — a mixture of brewer’s grain, Indian meal, oilcake and sometimes treacle or molasses. Water was, in my early years, fed by hand - it was late on in the life of Carisbrooke that automatic watering bowls were introduced. Writing now, 50 or 60 years on, you cannot escape the feeling that the modern RSPCA would not have looked on benevolently to the conduct and life of the cows once they reached Carisbrooke. Certainly the animals did not go outside the yard. And more often than not they never were allowed outside their stalls. Not until a deal was struck with a well-known cattle dealer, Rabinowitz, for the sale of an animal, for meat or possibly to be sold on for future husbandry elsewhere.

Thirty cows, milked twice a day, the milk certainly passing through a sieve to catch any deleterious matter, straw, hay, then it went straight into a 15 gallon churn. From this, milk would be ladled out and measured into tins of a pint capacity. Handles on the tins enabled you to carry six pints in each hand. The pint would be dumped onto the householder’s doorstep, a hearty kick on the door or a persistent ring of the bell, on to the next customer, and a fervent hope that the empty tin would await you on the return journey, so you could get more pints for more of the customers.

Also, there were the three horses. I can remember vividly two of the horses. First, ‘Muddle’ - originally a deep black mare. Father had one of his days off, went to Brough Hill Fair and came back with a present for Mother — a packet of needles and Muddle. How did it get its name? Well, in Father’s absence everything had gone wrong at home. When things had quietened down, he was asked what was the name of the horse — ‘Muddle’ he said, in desperation! I don’t know what age the horse would be when we got it – probably four or five years. I know that during the 1914-18 war officers from an artillery unit called, inspected the animal and finally decided it was not big enough to pull a gun carriage. So, Muddle remained. And when we sold Carisbrooke in 1934 one of the sale conditions I insisted upon was that Muddle was to stay on with the new purchaser, George Bargh, until its working days were over, then Bargh was to find a suitable place for our old friend to finish its days. This he respected implicitly.

But Muddle, which progressed from a jet-black coat to grey, even white in its later years, became one of the talked-of sights in Walton. Generally, Muddle was driven by either my youngest sister Peg or middle sister Ethel. Both were completely fearless. They drove at a thoroughly reckless pace when the milk round was over, to get back home as soon as possible. And one of our many dogs would always be present, barking and jumping excitedly at the horse’s head as it tore through the Walton roads.

Our other horse, Polly, was a different type of animal. I could get along with Polly, whereas I could never could get to grips with Peg or Ethel’s horse, they could do just what they liked with her. Polly came from the Isle of Man. Before she reached us she had never seen a busy road. The first time we took her out on the milk round she was a fretful beast to handle. First time a tramcar rumbled past she reared up, tried to bolt and I, who had been commissioned by Father to ‘hold her head’, was really scared and fearful of being injured. But I had been told what I had to do, and somehow held on. We kept Polly — she was many years younger than Muddle — and she was sold as an integral part of the sale of the dairy years later to Bargh.

We had a succession of other horses supplementing Muddle and Polly. I think, looking back, I was almost a ‘horse coper’. Generally a prospective buyer would arrive early in the morning, before school. I was hoisted onto the back of the animal - I always rode bareback - dug my knees in and with the aid of a stick whipped the horse into a good showing, to impress the buyer. Then I’d dismount, turn the animal over to Father and hurry off to catch the last tram to get me to the school before being marked late.

I was also brought into horse riding on a Wednesday afternoon - a half-day holiday from school. I was allowed to take one or other of the horses to the blacksmith for shoeing, because metal roads seemed to wear out a set of horseshoes every third week. Muddle I rarely rode. We had an uneasy truce on these days. I could lead her by the bridle, but never ventured to ride her.

A fascinating place was the blacksmith’s shop - near Walton Church, perhaps a mile from Carisbrooke. The blacksmith’s nose I recall so vividly - completely flat. Some horse patently had given him the full treatment.

Most horses were fairly settled and stood quiet, chained to an iron ring. I stood by and was really fascinated by the blacksmith’s trade. A heap of apparently dead coke was galvanised into a glowing red-hot fire by a few pumps on the bellows. Horseshoes were heated red hot, moulded onto the hoof of the horse, dropped hissing into a tub of cold water, straightened to size with a huge rasping file and then hammered onto the animal’s hooves by the muscular smith. And with it all the smell of burnt bone. I can almost smell the evidence of the smith’s trade even now.

And then, the mad dash home. Apart from Muddle that is - she and I would make our way decorously through the streets of Walton; but not so the others. They had the knowledge that when they got back to their stable a bag of oats awaited them. I had the knowledge that I might just get back in time for the matinee performance at the local cinema, the Bedford. So we needed no urging. The only time we had to show any restraint was when we had to cross the busy main road. Then it was ‘all stations go’ with the horse only coming to a halt as it reached the stable door.

We had hens, though not encouraged by Father. But, he did allow me to keep a few bantams. We also had cats, and dogs. These always seemed to get attached to me, they often slept in my bedroom. And certainly always joined me as I ran, yes, ran, with the milk round. This would start at seven o’clock and finish, for me, before eight o’clock. Then I would set off for school. And the dogs ran with me on the round, barking vigorously. Cans rattling and me hammering at doors as I dropped the tin of milk to make sure the inhabitants and customers had the tin emptied before I stopped to collect it on the way back. Once, we had to pacify some old dear who quite seriously was all set to report me to the police for committing an act of nuisance.”

“I think the construction of the new dairy at 134 Carisbrooke Road, Walton, Liverpool, needs some description. Not only for its grandiose construction (of those days), but because of the trade carried on. A trade long since ended.

First, the buildings. The main rooms on the ground floor - back kitchen, kitchen, dairy, and parlour – were all fair sized rooms. The back kitchen was where the meals were prepared. The kitchen was the centre of the world of ‘Carisbrooke’. The parlour was only used on festive occasions. And the dairy? Well, a certain amount of trade was done there, but not so very much, as we ‘went to the customer’, rather than vice versa. We had five bedrooms and commodious cellar, attic and hallway.

Perhaps more important and more of interest would be my description of the outbuildings — cowshed, stables, washhouse. Yes, we had a large washhouse, which was used for domestic purposes. Stables. Well, we had three horses, and adequately and well housed were these animals. Now, the cowshed (I wish I could use a more polite descriptive word, but I can’t. Cowshed it was to me in my youth, and cowshed it is now in old age). Shippon perhaps sounds better. Anyway in the shippon we had stalls for 32 cows. Our boast, I suppose, was that we sold milk straight from the cow to the customer. And on the yard between the shippon and the house we had a large brick-built midden to collect the manure from the cows. And in the yard, too, we kept the milk floats, two of them.

The midden or manure pit was not too oppressive a sight. It was emptied possibly twice a week by farmers from farms on the outskirts of Liverpool - potato and crop farmers, who would make an eight- to ten-mile journey each way to collect the manure. They used their own wagons for this purpose. One man, the driver, and our cowman would help load his wagon. Loads of three to five tons of manure each journey. And from memory, I sometimes made up the manure accounts. We got fifteen shillings a ton.

Above the cow stalls/stables a loft ran the whole length of the building. And we spent many happy hours playing amongst the baled hay — to the annoyance of Father who strongly and sometimes painfully expressed his annoyance at our noise upsetting his beloved cows.

So much for the bricks and mortar. Let me try and put some bones on this brief descriptive picture of Carisbrooke. Animals first. Every week — it seemed — Father would go off for the day to Preston Cattle Market. Sometimes he bought for himself, sometimes for other milkmen presumably on a commission basis. Sometimes he just went for the day out. Yes, Father liked his day off. Equally, whatever else, he was a very good judge of cattle and a good stock handler. In all my years at Carisbrooke I’ve no clear recollection of a ‘Vet’ coming near the premises. Father dosed and treated the cattle himself. He knew his job.

I got an early apprenticeship to the cattle trade. I think I must have been a little lad of seven, possibly eight years old, when Father awoke me about 5.00 am. I would think, initially, to go with him as company, but later to play a major part. The cows bought at Preston would be loaded into railway trucks on a Friday afternoon, travel to Liverpool and remain in the railway trucks overnight until we collected them on Saturday morning. Usually five/six cows, frightened out of their wits by the train noise and the other hideous noises of a city. Yes, when they were first let loose they just ran wild — madly. I was at the front, instructed to turn them, not let than get away. And armed only with a stick it took real courage to stand in front of five madly charging beasts. And when you had managed to get them in some order you could quickly find yourself trying to stop yet another stampede caused by that horrible clanging of a tram or steam-lorry passing by. It was to be many years before delivery by vehicles direct from market to purchaser was to ease my lot. But I learnt in a hard school. I don’t know which I feared most — a buffet in the ribs from a charging beast or Father’s quite vitriolic comments if I let one of his cows get away.

The cows at Carisbrooke were well housed and regularly fed. Their diet was good quality hay and ‘tubs’ — a mixture of brewer’s grain, Indian meal, oilcake and sometimes treacle or molasses. Water was, in my early years, fed by hand - it was late on in the life of Carisbrooke that automatic watering bowls were introduced. Writing now, 50 or 60 years on, you cannot escape the feeling that the modern RSPCA would not have looked on benevolently to the conduct and life of the cows once they reached Carisbrooke. Certainly the animals did not go outside the yard. And more often than not they never were allowed outside their stalls. Not until a deal was struck with a well-known cattle dealer, Rabinowitz, for the sale of an animal, for meat or possibly to be sold on for future husbandry elsewhere.

Thirty cows, milked twice a day, the milk certainly passing through a sieve to catch any deleterious matter, straw, hay, then it went straight into a 15 gallon churn. From this, milk would be ladled out and measured into tins of a pint capacity. Handles on the tins enabled you to carry six pints in each hand. The pint would be dumped onto the householder’s doorstep, a hearty kick on the door or a persistent ring of the bell, on to the next customer, and a fervent hope that the empty tin would await you on the return journey, so you could get more pints for more of the customers.

Also, there were the three horses. I can remember vividly two of the horses. First, ‘Muddle’ - originally a deep black mare. Father had one of his days off, went to Brough Hill Fair and came back with a present for Mother — a packet of needles and Muddle. How did it get its name? Well, in Father’s absence everything had gone wrong at home. When things had quietened down, he was asked what was the name of the horse — ‘Muddle’ he said, in desperation! I don’t know what age the horse would be when we got it – probably four or five years. I know that during the 1914-18 war officers from an artillery unit called, inspected the animal and finally decided it was not big enough to pull a gun carriage. So, Muddle remained. And when we sold Carisbrooke in 1934 one of the sale conditions I insisted upon was that Muddle was to stay on with the new purchaser, George Bargh, until its working days were over, then Bargh was to find a suitable place for our old friend to finish its days. This he respected implicitly.

But Muddle, which progressed from a jet-black coat to grey, even white in its later years, became one of the talked-of sights in Walton. Generally, Muddle was driven by either my youngest sister Peg or middle sister Ethel. Both were completely fearless. They drove at a thoroughly reckless pace when the milk round was over, to get back home as soon as possible. And one of our many dogs would always be present, barking and jumping excitedly at the horse’s head as it tore through the Walton roads.

Our other horse, Polly, was a different type of animal. I could get along with Polly, whereas I could never could get to grips with Peg or Ethel’s horse, they could do just what they liked with her. Polly came from the Isle of Man. Before she reached us she had never seen a busy road. The first time we took her out on the milk round she was a fretful beast to handle. First time a tramcar rumbled past she reared up, tried to bolt and I, who had been commissioned by Father to ‘hold her head’, was really scared and fearful of being injured. But I had been told what I had to do, and somehow held on. We kept Polly — she was many years younger than Muddle — and she was sold as an integral part of the sale of the dairy years later to Bargh.

We had a succession of other horses supplementing Muddle and Polly. I think, looking back, I was almost a ‘horse coper’. Generally a prospective buyer would arrive early in the morning, before school. I was hoisted onto the back of the animal - I always rode bareback - dug my knees in and with the aid of a stick whipped the horse into a good showing, to impress the buyer. Then I’d dismount, turn the animal over to Father and hurry off to catch the last tram to get me to the school before being marked late.

I was also brought into horse riding on a Wednesday afternoon - a half-day holiday from school. I was allowed to take one or other of the horses to the blacksmith for shoeing, because metal roads seemed to wear out a set of horseshoes every third week. Muddle I rarely rode. We had an uneasy truce on these days. I could lead her by the bridle, but never ventured to ride her.

A fascinating place was the blacksmith’s shop - near Walton Church, perhaps a mile from Carisbrooke. The blacksmith’s nose I recall so vividly - completely flat. Some horse patently had given him the full treatment.

Most horses were fairly settled and stood quiet, chained to an iron ring. I stood by and was really fascinated by the blacksmith’s trade. A heap of apparently dead coke was galvanised into a glowing red-hot fire by a few pumps on the bellows. Horseshoes were heated red hot, moulded onto the hoof of the horse, dropped hissing into a tub of cold water, straightened to size with a huge rasping file and then hammered onto the animal’s hooves by the muscular smith. And with it all the smell of burnt bone. I can almost smell the evidence of the smith’s trade even now.

And then, the mad dash home. Apart from Muddle that is - she and I would make our way decorously through the streets of Walton; but not so the others. They had the knowledge that when they got back to their stable a bag of oats awaited them. I had the knowledge that I might just get back in time for the matinee performance at the local cinema, the Bedford. So we needed no urging. The only time we had to show any restraint was when we had to cross the busy main road. Then it was ‘all stations go’ with the horse only coming to a halt as it reached the stable door.

We had hens, though not encouraged by Father. But, he did allow me to keep a few bantams. We also had cats, and dogs. These always seemed to get attached to me, they often slept in my bedroom. And certainly always joined me as I ran, yes, ran, with the milk round. This would start at seven o’clock and finish, for me, before eight o’clock. Then I would set off for school. And the dogs ran with me on the round, barking vigorously. Cans rattling and me hammering at doors as I dropped the tin of milk to make sure the inhabitants and customers had the tin emptied before I stopped to collect it on the way back. Once, we had to pacify some old dear who quite seriously was all set to report me to the police for committing an act of nuisance.”

Parents - Edward and Mary Mason © Robert Mason 2018

Parents - Edward and Mary Mason © Robert Mason 2018

Father – Edward Mason

“Father was of autocratic type. You never questioned his decisions. He was the head of the house and what he said went. He was respected for his knowledge and his ability with animals. His day, broadly, would start at 7.00 am. Rise, and if anyone had made a cup of tea by then, he would join in. If not, Mother or one of the girls would take him a cup into the shippon. They also would take one to the hired man — like horses, we had a series of them over the years - and also a cup to Hannah, my eldest sister. She was not involved with the milk round, unless someone was ill. No, she was very much part of the life in the shippon: milked cows with the best; fed and watered; anything to do with cattle.

So, milking over, Father would come in for breakfast, wash and change and then set off on his milk round. You will note I did not say ‘wash and shave’, he never shaved himself. The day of the safety razor had yet to dawn. And when it did Father was too set in his ways to change to these new fangled ideas. No, each day he used to go to a barber, Quillam, in Walton, who shaved him; sort of on a quid pro quo basis — milk for a shave.

I would be expected to go with Father on the milk round if I was not at school - holidays, half term and of course Sunday mornings. The latter I disliked. Not that I did not want to deliver milk. But because when Father finished his milk round he made for the nearest of his favourite pubs — the ‘County’, Black Horse or Glebe. I was left outside with the pony and milk float, until Father decided to reappear having set the world to right with his cronies and consumed his daily beer allowance. Then we would go home for Sunday dinner. Somehow on the way he would have bought a bag of sweets for Mother, always the same, hard toffees, which she disliked. And if he was late for Sunday lunch the sweets were thrown angrily down on the table, but we children saw they were never wasted.”

Mother – Mary Ewbank

“Mother was a gentle, kindly lady, loved by all. In her latter years she was a sick woman, diabetes, but her early years must have been like a chapter of pioneering life. Her maiden name was Ewbank, her mother had married a Chris Ewbank from the ‘Temple’ branch of the Ewbank family at Aysgarth, North Yorkshire. This lady’s name before her marriage was Pratt. She had two brothers, Uncle Richard Pratt at Skibden Farm outside Skipton, and Uncle Jim Pratt who farmed at Chapel House, Burtersett, near Hawes.

It would be quite soon after the arrival of Chris Ewbank’s family in Liverpool that he died — erysipelas originating, I was told, in his nose. And you can imagine the position Grandmother Ewbank was to be forced into. A young widow with a large family — three boys and three girls by this time and a dairy business to run. Mother could only have been in her early teens and Uncle Tom not so very much older. But to his everlasting credit, Uncle Jim Pratt from Burtersett stepped into the breach. He was quite a young man and had recently started farming and cattle dealing. He came down to Liverpool and for practically all of the first year after grandfather’s death, helped his sister to run the business and to help rear a young family.”

Sisters - Hannah, Peg and Ethel c. 1907 © Robert Mason 2018

Sisters - Hannah, Peg and Ethel c. 1907 © Robert Mason 2018

Siblings

“So now, briefly we turn to the brother and sisters that I was privileged to grow up with. In all there were five of us, Hannah, Ethel, Peg, George and myself.

Hannah would be eight or possibly nine years older than me. I don’t think the other two sisters would disagree, nor be jealous when I said she was like a second mother to me. As a young girl she was a first-class tomboy. She had no inhibitions about setting to and fighting or sparring with any of the hired men and gave as good as she got. And they were never discourteous or attempted to take any advantage of her. She was defensive so far as we needed it. Her duties were primarily as second assistant in the work of the shippon. She could milk probably better than anyone else. I don’t recall that she had any particular affinity with the horses. On business matters connected with the dairy, sickness of cattle or parallel problems she was I think, Father’s first confidante. I think if he admired any one of his children more than the other, it was Hannah. Now, I don’t say he loved this child more than the others - that would not be fair. Purposely I say ‘admired’.

Ethel, in her early teens was something of a mystic, a dreamer. She had a penchant for getting into trouble. She caught typhoid thought to be from eating ice cream. She had numerous falls or accidents, broke her collarbone from falling off a horse. She showed her liking for cooking at a very early age, never happier than when she was making a meal, a new dish, trying out a new recipe. Ethel had a wonderful way with horses. I can see her now driving the milk float like a Roman chariot - horse galloping for dear life. She never seemed to hold the horse’s head on a tight rein, just let them hang loose. Never vicious, but somehow, almost instinctively, the horses would respond and give of their best.

I suppose if you were trying to sum up the character of Peg, my youngest sister, you would say she was the lady of the family. Not that this is in any way deprecating the other two girls, but Peg took more time over her dress. She always appeared well turned out. Even on a cold winter with heavy rain about she looked neat and tidy.

As for me, I had started at Arnot Street School - an elementary school - sometime after my fifth birthday. I was to stay at Arnot Street until I was 11, when I went on to the Collegiate School, Shaw Street, Liverpool.”

“So now, briefly we turn to the brother and sisters that I was privileged to grow up with. In all there were five of us, Hannah, Ethel, Peg, George and myself.

Hannah would be eight or possibly nine years older than me. I don’t think the other two sisters would disagree, nor be jealous when I said she was like a second mother to me. As a young girl she was a first-class tomboy. She had no inhibitions about setting to and fighting or sparring with any of the hired men and gave as good as she got. And they were never discourteous or attempted to take any advantage of her. She was defensive so far as we needed it. Her duties were primarily as second assistant in the work of the shippon. She could milk probably better than anyone else. I don’t recall that she had any particular affinity with the horses. On business matters connected with the dairy, sickness of cattle or parallel problems she was I think, Father’s first confidante. I think if he admired any one of his children more than the other, it was Hannah. Now, I don’t say he loved this child more than the others - that would not be fair. Purposely I say ‘admired’.

Ethel, in her early teens was something of a mystic, a dreamer. She had a penchant for getting into trouble. She caught typhoid thought to be from eating ice cream. She had numerous falls or accidents, broke her collarbone from falling off a horse. She showed her liking for cooking at a very early age, never happier than when she was making a meal, a new dish, trying out a new recipe. Ethel had a wonderful way with horses. I can see her now driving the milk float like a Roman chariot - horse galloping for dear life. She never seemed to hold the horse’s head on a tight rein, just let them hang loose. Never vicious, but somehow, almost instinctively, the horses would respond and give of their best.

I suppose if you were trying to sum up the character of Peg, my youngest sister, you would say she was the lady of the family. Not that this is in any way deprecating the other two girls, but Peg took more time over her dress. She always appeared well turned out. Even on a cold winter with heavy rain about she looked neat and tidy.

As for me, I had started at Arnot Street School - an elementary school - sometime after my fifth birthday. I was to stay at Arnot Street until I was 11, when I went on to the Collegiate School, Shaw Street, Liverpool.”

Chapel Farm, Burtersett - 2004 © Robert Mason 2018

Chapel Farm, Burtersett - 2004 © Robert Mason 2018

Holidays at Burtersett

“But, I think before I proceed with the fortunes of the ‘Family’ any further, I would like, briefly, to touch on Burtersett, near Hawes, and all it was to mean to me.

It was the first long summer holiday of my first year at the Collegiate. We would finish school about 20/23 July, and not be due to return until early September. So my first acquaintance with Burtersett would be July 1922 and I would be 13. Father, or more likely Mother, had arranged with Uncle Jim Pratt at Burtersett (Mother’s uncle) that I would go there as a farm lad for my seven weeks summer holiday. Father had no difficulty in arranging to get me there. He and I and a Mr Lunt from the paint shop, all travelled in Harry Mason’s car up to Burtersett. The latter was the publican from the County Hotel. It was a perfect summer day. We stopped at Sedbergh for lunch and sometime in the early afternoon we all arrived at Chapel House Farm, Burtersett, Hawes where Uncle Jim Pratt, Aunt Rose his wife, their two sons, James and Richard, farmed. They had a daughter also, Annie, who would be about five years older than me. At this time Annie had not broken up from boarding school.

I was introduced to haymaking at Wilsons Field in Burtersett. In a modest way I helped collect the dried hay for loading into the barn. And about 5.00/6.00 o’clock we had finished the field. Good. I thought. That’s it for the night. But, I was wrong. When Wilsons Field was finished we all trooped down to Lowside and worked on well into the dusk. It was a tired little boy who climbed into bed in a room I shared with Jim and Richard — who would be in their early twenties then, both unmarried.

A few words about the Pratt’s farm at Burtersett. I should say it was quite a fair-sized Dales farm, certainly very extensive. They had top pastures on Yorburgh and Wether Fell — the latter a mountain of over 2,000 feet. Fields and farmlands in the village at Burtersett, and pastures and fields stretching down to the banks of the River Ure in the valley below. My days there in the 1920s were long before tractors and mechanisation. The nearest they got to the latter was a two-horse-drawn mower. And it was interesting to see the Pratts’ horses coming off the top pasture, sleek, well fed and then at the end of hay time patently a good deal slimmer.

The farm was run by Uncle Jim, at that time I suppose in his early 60s, and the two Pratt lads, Jim and Richard. And to augment the workforce there was the handyman, Will Chapman. Will had a smallholding. Lived with his sister and father and was almost a daily worker for Uncle Jim. I don’t know what the terms of payment would be. I do know that at sometime in hay time we all moved over to the Chapman fields and cut his hay for Will. He could turn his hand to most things, could Will - anything mechanical or needing a modicum of engineering skill. Not outstanding with cattle, but joinery, yes, first class.

And then in hay time there were the Irishmen. Always two, sometimes three, hired men. They would be hired for say two to three months at the market in Hawes. One of them, Martin, was a regular visitor, came every year. So far as I could judge the progress of the Irishman was a stint in Lancashire for the hay, the Dales for their hay time, the East coast for the corn crop, back to Lancashire for the potato lifting, then back to Ireland. They would have their meals in the farmhouse and Aunt Rose would do a modest amount of washing for them. But, they slept over a cow byre in a building some 50/100 yards away. Good workers. Needed no driving. They just got on with the job. And if the weather was threatening and a load of hay still to be collected, well, out came the beer, drawn from a large hogshead in Chapel House Farm. Yes that expedited the work. We never worked on Sundays - at least very, very rarely. So far as the Irishman were concerned they went their own way for the Sunday.

As for the Pratts (and myself), well, Sunday morning after milking was done I would go with Richard usually up the fell, shepherding, looking at their cattle grazing on the top pastures; always accompanied by the two sheepdogs, Spring and Lady. Spring was just disdainful so far as I was concerned. But, Lady (Spring’s daughter) was a different dog. We were inseparable. And struck up a working friendship. At that time I was a fair runner. And what I lacked in skill of sheepdog running we more than made up this lack of knowledge in the sheer enthusiasm of the pair of us.

The Pratts would have about 200 breeding ewes — Scotch black-faced sheep and a few ‘Mugs’ or Swaledale sheep. They would lamb the pure bred ‘Scotch-faced yins’ or use a ‘Mug’ tup to produce a ‘half-bred gimmer’. The lambs would be fed on until the lamb sales, September onwards, then sold off at Hawes Auction Mart for meat purposes mainly.

Cattle, well they were usually young cattle, first or second calvers. They in turn would be sold at the auction mart, and the calved cows would find their way to the Lancashire dairies or farms eventually.

Milking was an odd, almost archaic, method compared to modern milking. The cows would be housed in the many barns on the farm, particularly so in the winter months. You have to think of the hay being cut and stored in the barns. And the cows came in turn and were fed from the hay above in the lofts so that there could be as many as 20-30 stock in different locations. Milking was by hand. When the cow had been milked the pail was emptied into a ‘budget’, a form of milk churn that was carried manually back to Chapel House where it was cooled and refrigerated and put into a 10/15-gallon tank. In the early years we — or a neighbouring farmer — took the milk to Hawes railway station. It would be some years before the advent of the milk-collecting wagon. Equally with cattle - no cattle truck collection for the markets. No, it was all a question of driving the cattle to the market.

I was to stay that first holiday for seven weeks. At the end I said ‘Goodbye’ to Aunt Rose and the Pratts with genuine tears in my eyes. And Aunt Rose (and Uncle Jim) made it abundantly clear that any time I wanted to come and stay with them I just had to write and say so. And this I did for many summers ahead, and also at Easter. Burtersett became my second home.

The dairy at Carisbrooke carried on quite well in my absence but I would quickly slip into the old routine: milk round between 7 and 8.00 o’clock (am); tram, bicycle or walk to the Collegiate, two or three miles away; lessons; return home for homework and then out to play until about 9.00 o’clock or later.”

“But, I think before I proceed with the fortunes of the ‘Family’ any further, I would like, briefly, to touch on Burtersett, near Hawes, and all it was to mean to me.

It was the first long summer holiday of my first year at the Collegiate. We would finish school about 20/23 July, and not be due to return until early September. So my first acquaintance with Burtersett would be July 1922 and I would be 13. Father, or more likely Mother, had arranged with Uncle Jim Pratt at Burtersett (Mother’s uncle) that I would go there as a farm lad for my seven weeks summer holiday. Father had no difficulty in arranging to get me there. He and I and a Mr Lunt from the paint shop, all travelled in Harry Mason’s car up to Burtersett. The latter was the publican from the County Hotel. It was a perfect summer day. We stopped at Sedbergh for lunch and sometime in the early afternoon we all arrived at Chapel House Farm, Burtersett, Hawes where Uncle Jim Pratt, Aunt Rose his wife, their two sons, James and Richard, farmed. They had a daughter also, Annie, who would be about five years older than me. At this time Annie had not broken up from boarding school.

I was introduced to haymaking at Wilsons Field in Burtersett. In a modest way I helped collect the dried hay for loading into the barn. And about 5.00/6.00 o’clock we had finished the field. Good. I thought. That’s it for the night. But, I was wrong. When Wilsons Field was finished we all trooped down to Lowside and worked on well into the dusk. It was a tired little boy who climbed into bed in a room I shared with Jim and Richard — who would be in their early twenties then, both unmarried.

A few words about the Pratt’s farm at Burtersett. I should say it was quite a fair-sized Dales farm, certainly very extensive. They had top pastures on Yorburgh and Wether Fell — the latter a mountain of over 2,000 feet. Fields and farmlands in the village at Burtersett, and pastures and fields stretching down to the banks of the River Ure in the valley below. My days there in the 1920s were long before tractors and mechanisation. The nearest they got to the latter was a two-horse-drawn mower. And it was interesting to see the Pratts’ horses coming off the top pasture, sleek, well fed and then at the end of hay time patently a good deal slimmer.

The farm was run by Uncle Jim, at that time I suppose in his early 60s, and the two Pratt lads, Jim and Richard. And to augment the workforce there was the handyman, Will Chapman. Will had a smallholding. Lived with his sister and father and was almost a daily worker for Uncle Jim. I don’t know what the terms of payment would be. I do know that at sometime in hay time we all moved over to the Chapman fields and cut his hay for Will. He could turn his hand to most things, could Will - anything mechanical or needing a modicum of engineering skill. Not outstanding with cattle, but joinery, yes, first class.

And then in hay time there were the Irishmen. Always two, sometimes three, hired men. They would be hired for say two to three months at the market in Hawes. One of them, Martin, was a regular visitor, came every year. So far as I could judge the progress of the Irishman was a stint in Lancashire for the hay, the Dales for their hay time, the East coast for the corn crop, back to Lancashire for the potato lifting, then back to Ireland. They would have their meals in the farmhouse and Aunt Rose would do a modest amount of washing for them. But, they slept over a cow byre in a building some 50/100 yards away. Good workers. Needed no driving. They just got on with the job. And if the weather was threatening and a load of hay still to be collected, well, out came the beer, drawn from a large hogshead in Chapel House Farm. Yes that expedited the work. We never worked on Sundays - at least very, very rarely. So far as the Irishman were concerned they went their own way for the Sunday.

As for the Pratts (and myself), well, Sunday morning after milking was done I would go with Richard usually up the fell, shepherding, looking at their cattle grazing on the top pastures; always accompanied by the two sheepdogs, Spring and Lady. Spring was just disdainful so far as I was concerned. But, Lady (Spring’s daughter) was a different dog. We were inseparable. And struck up a working friendship. At that time I was a fair runner. And what I lacked in skill of sheepdog running we more than made up this lack of knowledge in the sheer enthusiasm of the pair of us.

The Pratts would have about 200 breeding ewes — Scotch black-faced sheep and a few ‘Mugs’ or Swaledale sheep. They would lamb the pure bred ‘Scotch-faced yins’ or use a ‘Mug’ tup to produce a ‘half-bred gimmer’. The lambs would be fed on until the lamb sales, September onwards, then sold off at Hawes Auction Mart for meat purposes mainly.

Cattle, well they were usually young cattle, first or second calvers. They in turn would be sold at the auction mart, and the calved cows would find their way to the Lancashire dairies or farms eventually.

Milking was an odd, almost archaic, method compared to modern milking. The cows would be housed in the many barns on the farm, particularly so in the winter months. You have to think of the hay being cut and stored in the barns. And the cows came in turn and were fed from the hay above in the lofts so that there could be as many as 20-30 stock in different locations. Milking was by hand. When the cow had been milked the pail was emptied into a ‘budget’, a form of milk churn that was carried manually back to Chapel House where it was cooled and refrigerated and put into a 10/15-gallon tank. In the early years we — or a neighbouring farmer — took the milk to Hawes railway station. It would be some years before the advent of the milk-collecting wagon. Equally with cattle - no cattle truck collection for the markets. No, it was all a question of driving the cattle to the market.

I was to stay that first holiday for seven weeks. At the end I said ‘Goodbye’ to Aunt Rose and the Pratts with genuine tears in my eyes. And Aunt Rose (and Uncle Jim) made it abundantly clear that any time I wanted to come and stay with them I just had to write and say so. And this I did for many summers ahead, and also at Easter. Burtersett became my second home.

The dairy at Carisbrooke carried on quite well in my absence but I would quickly slip into the old routine: milk round between 7 and 8.00 o’clock (am); tram, bicycle or walk to the Collegiate, two or three miles away; lessons; return home for homework and then out to play until about 9.00 o’clock or later.”

The End of School Years

“Father said he thought he had arranged for me to go for an interview with the ‘Globe’, an insurance company in Dale Street… I was duly called for interview… a week later I got my appointment letter to start as a junior clerk on August 25th 1925 at the princely annual salary of £45. I hurriedly wrote my letter of acceptance and then went off to Burtersett for two weeks’ holiday before I started.”

“Father said he thought he had arranged for me to go for an interview with the ‘Globe’, an insurance company in Dale Street… I was duly called for interview… a week later I got my appointment letter to start as a junior clerk on August 25th 1925 at the princely annual salary of £45. I hurriedly wrote my letter of acceptance and then went off to Burtersett for two weeks’ holiday before I started.”

The Decline of Carisbrooke Dairy

“I think you could say the fortunes of the dairy at ‘Carisbrooke’ declined slowly but inexorably from 1925 onwards. The reasons were not far to seek. The house-building, which had been envisaged beyond Carisbrooke Road and stretching into Bootle, just did not come about. In fact it was to be well after the 1939-1945 War and beyond before the field where we played — known as the ‘Brickfield’ — was to be built upon. And too, we had the Depression years when unemployment took its toll and good customers were either forced to go to the cheaper markets or just take less milk.

But, even worse was the action of the Liverpool Co-operative Society who had a grocery store opposite and decided to go in for milk also. They built an up-to-date dairy and started to sell cheap milk in strong competition. Father tried to enlist the support of the landowner — the old Earl of Derby. He had an interview, but naturally, Lord Derby, sympathetic though he may have been, could not realistically help. And in the middle of Carisbrooke Road, right in front of our premises, a huge shaft was sunk into the ground - I think this could have been in conjunction with sewage - and it screened off old customers, many of them old friends, from sight of ourselves, so that they could with impunity take their custom to our hated rivals.

Yes, unhappy days. Days that worried my mother, most of all. Father must have been concerned, but he did not show it and continued in his old way of life. And, I think when funds got low and the tradesmen started to press that bit harder, he went to an accommodating bank manager and got further overdraft against the Carisbrooke Road premises.

Yet, we children all had something going for us — with the possible exception of brother George. Hannah would be the first to break away. On a holiday in the Isle of Man Hannah and Ethel had met two brothers. She said to Ethel ‘I’ll have the dark one, you take the other.’ And so it all happened. In 1926 Hannah married George Pickup and set up home in Aintree at Danehurst Road. And then, in 1930, Ethel married Henry Pickup. Also that year, Peg married Everton footballer, Jasper Kerr.

Brother, George Mason © Robert Mason 2018

Brother, George Mason © Robert Mason 2018

But, we then had two very sad events in our little world. In 1932 Mother died. She had suffered ill health for some years - kidney trouble I think would be the start. And Father was never the same afterwards. He was to survive Mother by only two years.

Vividly I recall the last few months of Father’s life. It would be in the September 1933 that he set off on one of his beloved days out to Lancaster Cattle Show. And it was from there we learnt he had had a stroke and had been taken to Lancaster lnfirmary. He was to remain there for three weeks. And I spent a fair bit of that time travelling to and from Lancaster, staying overnight at the ‘Farmers Arms’, Lancaster. Eventually we got him back by ambulance to ‘Carisbrooke’ and for six months he was a very sick man.

Henry, George and I took time sitting up at night with him, but the bulk of the work would fall on Ethel. Hannah and Peg, who were living in their own homes, certainly came and helped whenever possible, but Ethel was the solid support, looking after Father, housekeeping and helping in the dairy. George, who would then be only 16/17 was ‘thrown in at the deep end’ when he had the affairs of Carisbrooke to conduct. I was there, I suppose, to help in whatever way possible, but this could only be out of business hours — when I had finished working in the daytime with the ‘Globe’.

Father died in March 1934. It was only after the funeral when I started to collate the debt, that I realised the somewhat horrendous extent of the monies owing to many creditors. The bank was the major creditor. Then we had cattle food merchants’ debts.

Well, it is a true saying, ‘when one door shuts another door opens’. And so it proved to be the case. We found a purchaser in a distant cousin, George Bargh. He had a dairy in Walton Village. Yes, he would buy at the right price. Yes, he would be only too happy to continue to employ brother George. And this seemed quite a good prospect for George inasmuch as the Barghs had no family and they would, I thought, treat George fairly well — as proved to be the case.

By the time the debts were paid over, the reduced overdraft liquidated, the monies left over from the sale of Carisbrooke was about £300. I wrote a letter, and the three girls agreed and signed to that effect, that George took all of the £300. Incidentally, there was not a great amount of furniture to dispose of. The best pieces had gone — the girls by arrangement had taken what they wanted. My acquisitions from this source were indeed very modest.

So ended the episode of Carisbrooke. And the memories? Pre-eminently happy ones. Certainly we children had never gone short. We may have had worries, but we had been a contented family and when in latter years we foregather as a family, we always had some memory to laugh over. Yes, happiness, I think, was a strong thread running through ‘Carisbrooke’.”

**********

As well as communicating his personal frustration at the closure and subsequent sale of the family business, a letter written by Edward Ewbank Mason in April 1934, also reflects the difficulties being faced by all of the city cowkeepers at that time – struggling to continue in the face of sweeping changes in the dairy market. The text of that letter is reproduced below:

134 Carisbrooke Road

Walton, Liverpool

27th April 1934

To whosoever hereafter it may concern:-

Today the sale of my father’s business, stock, goodwill and property situate as above was completed at the price of:-

To any critics or the like it is well to divulge the following facts.

In conversation with the former Bank Manager, Mr Owens, he gave me grace until the end of April to ‘do best as possible’. At the end of March 1934 he subsequently retired. His grace or assurances were of no practical value. I have no doubt that the Bank would have foreclosed, had a forced sale and probably my father would have been in the same position of a Bankrupt i.e. owing debts to the extent of £600. This assumption has subsequently been confirmed from several sources, but particularly from an employee of the aforesaid Bank who in confidence, stated that they, the Bank, ‘would have been satisfied if they had got £1100 of the amount of £1400 owing’.

My brother, George has been found a good home and I trust regular and good employment and I hope that in some seven or eight years hence he is able to start on his own accord as a Dairyman (with more success than his Father) and Cowkeeper himself. My sister Ethel is relieved of all responsibility of staying here and is able to start house on her own – which I think, is a private sentiment she has nursed for some years.

As a concluding statement at the price of 6d per quart of milk we definitely were losing money and this business was not paying for itself. Milk as from the 1st May 1934 was reduced to 5½d per quart. The last sentence is added ‘without comment’. The Milk Marketing Board are working for the large firms, for example, Co-operatives and in a few years I do not have any hesitation in stating that the number of firms will be greatly reduced. Our firm – Edward Mason, Cowkeeper and Dairyman – would have been wiped out in a few months!

So, any person or persons who may criticise my action in selling take careful note of the foregoing factors and judge accordingly.

Edward Ewbank Mason

Witnessed by:-

George D Mason

Henry Pickup

134 Carisbrooke Road

Walton, Liverpool

27th April 1934

To whosoever hereafter it may concern:-

Today the sale of my father’s business, stock, goodwill and property situate as above was completed at the price of:-

- £1600 for the business

- £50 to be credited to my brother, George Mason’s account

- We, to retain all provender – which was subsequently sold for £6 - and also the two horses

- My brother George Mason to be retained in the employment of the Purchaser

To any critics or the like it is well to divulge the following facts.

- There was an outstanding mortgage with the Midland Bank of £1395

- There were sundry creditors to the extent of £300

In conversation with the former Bank Manager, Mr Owens, he gave me grace until the end of April to ‘do best as possible’. At the end of March 1934 he subsequently retired. His grace or assurances were of no practical value. I have no doubt that the Bank would have foreclosed, had a forced sale and probably my father would have been in the same position of a Bankrupt i.e. owing debts to the extent of £600. This assumption has subsequently been confirmed from several sources, but particularly from an employee of the aforesaid Bank who in confidence, stated that they, the Bank, ‘would have been satisfied if they had got £1100 of the amount of £1400 owing’.

My brother, George has been found a good home and I trust regular and good employment and I hope that in some seven or eight years hence he is able to start on his own accord as a Dairyman (with more success than his Father) and Cowkeeper himself. My sister Ethel is relieved of all responsibility of staying here and is able to start house on her own – which I think, is a private sentiment she has nursed for some years.

As a concluding statement at the price of 6d per quart of milk we definitely were losing money and this business was not paying for itself. Milk as from the 1st May 1934 was reduced to 5½d per quart. The last sentence is added ‘without comment’. The Milk Marketing Board are working for the large firms, for example, Co-operatives and in a few years I do not have any hesitation in stating that the number of firms will be greatly reduced. Our firm – Edward Mason, Cowkeeper and Dairyman – would have been wiped out in a few months!

So, any person or persons who may criticise my action in selling take careful note of the foregoing factors and judge accordingly.

Edward Ewbank Mason

Witnessed by:-

George D Mason

Henry Pickup