Following the posting of my article about the Hogg family, ‘Hoggs, Herds and Cows’, I was contacted by Angela Hallows, the daughter of Thomas Leslie Hogg. Angela had a wealth of information about the life and times of her father, keeping cows in Aigburth, which she kindly offered to help fill out some gaps in the original article. The information comprised of Thomas’s memoirs, Angela’s memories and press articles about the family’s dairy in Alwyn Street. Upon reading, it quickly became apparent that rather than using this information to fill some gaps, it deserved to be published in its entirety — as a tribute to one of Liverpool’s last great cowkeepers.

Thomas Leslie Hogg (1906-1989) was one of the sons of John Hogg (1872-1953) and Mary Ellis (1877-1963). John and Mary married in May 1900 and soon afterwards, when John’s father relocated to Jericho Farm, they took over the running of the dairy at 3 BACK PARKFIELD ROAD, known as Parkfield Farm.

Thomas Leslie Hogg (1906-1989) was one of the sons of John Hogg (1872-1953) and Mary Ellis (1877-1963). John and Mary married in May 1900 and soon afterwards, when John’s father relocated to Jericho Farm, they took over the running of the dairy at 3 BACK PARKFIELD ROAD, known as Parkfield Farm.

Life at Parkfield Farm, 1906-1937, by Thomas L Hogg

“I was born on a ‘Town Farm’ in the Aigburth district of Liverpool, near Sefton Park. It was a life that was both Town and Country: meeting the people of this great city each and every day as we delivered our Ever-So-Fresh Milk; and, the trips into the country with Father when he went to buy cattle -- sometimes direct from the farm and other times at the cattle markets of Chester, Penrith, Kendal, Kirkby Stephen, Oswestry, Hawes and Leyburn in Yorkshire. These were wonderful days out for me as I was being educated in the art of valuing beasts, always trying to pick the one that would give a good yield of good milk when she reached her new home in town.

We were a family of seven Mother, Dad, three Brothers, one sister and myself; one brother died of diphtheria, one very sad Christmas morning. My earliest recollections involve father always having a job for us. He worked us very hard and he gave us just a small amount of pocket money to spend; actually it was a job to find the time to spend it. But he liked us to get finished in good time at night, say 6 o’clock. He used to shout “if you’re going hout, get hout and get back in again for bed or you’ll never get hup in the morning”. In the morning he was like a raving lunatic if we overslept until ten past five. He’d holler “now we’ve mucked it, we cant be hout with that milk by seven.” And that was almost ‘Holy Orders’ with him, to be driving down the yard in the float with the tanks of milk and cans as the clock struck 7. If the rival firm ever reached the corner of Alexandra Drive before us he made it sound as though we were ruined. Just imagine asking men today to milk 32 cows (by hand) and when you milk them for father they must be washed, dried and absolutely free from loose dirt or hairs. I will always think that he was one of the cleanest milk producers ever. He really had the public interest at heart and he was not shy to tell us if his quick eye saw a dirty milking stool that may in turn dirty the hand that goes so near the milk.

Mother did the washing up with the help of a hired girl when available. I have memories of the kitchen floor being covered with tanks and cans all to wash, scald and dry, as was the practice in those days. At the same time, she would look after the dairy, make the beds and I never remember waiting for a meal when I came home from school or during all the years that followed. She was a marvel, always so bright, singing whilst working most of the time. Then in the comparative quiet of the afternoon, with only the dairy to look after, she would make out all the milk accounts, each in a small book (one for each individual customer).

My eldest brother Jack was very strong and it would be fair to say that he did most of the milking of the ‘hard’ cows. It always meant disappointment when one of the best cows had a teat trodden on, making it sore and hard to milk. That trouble must have cost the Liverpool farmer thousands of pounds in time and milk and sometimes loss of a cow, as inflammation was not so easy to conquer in those days without the penicillin and the antibiotics that we have today.

From 1874 onwards, nearby Sefton Park was our ‘farm’ for over fifty years. The men of Parks and Gardens would mow the grass 5½ days a week and we would rake it up and cart it away to the cows. We soon found out that one of the secrets of feeding grass to milk cattle is to feed it as soon after mowing as possible. We always found the cows gave less milk on Monday morning when we were feeding them grass that had been cut on Friday and Saturday; Father always arranged, with the co-operation of the park men, to mow the thickest grass on Friday afternoon and Saturday morning, to do us over the weekend. I always went to the park about 8:30 am on Monday morning in grass time and one of my most pleasant recollections is the memory of the sweet smell of the grass mown with the dew still on it. It must surely be one of nature’s very best. On Saturdays we always tried to get a very big load to have some reserves for Sunday. I had the job of loading the wagon and it had to be done so well that not one blade would fall off on the roads, which all had to be swept ‘lovely’ for Sunday. So, you can imagine the time that was spent, after the full load was on the wagon, raking down and pulling the loose bits off by hand to make absolutely sure none would fall on the park roads."

We were a family of seven Mother, Dad, three Brothers, one sister and myself; one brother died of diphtheria, one very sad Christmas morning. My earliest recollections involve father always having a job for us. He worked us very hard and he gave us just a small amount of pocket money to spend; actually it was a job to find the time to spend it. But he liked us to get finished in good time at night, say 6 o’clock. He used to shout “if you’re going hout, get hout and get back in again for bed or you’ll never get hup in the morning”. In the morning he was like a raving lunatic if we overslept until ten past five. He’d holler “now we’ve mucked it, we cant be hout with that milk by seven.” And that was almost ‘Holy Orders’ with him, to be driving down the yard in the float with the tanks of milk and cans as the clock struck 7. If the rival firm ever reached the corner of Alexandra Drive before us he made it sound as though we were ruined. Just imagine asking men today to milk 32 cows (by hand) and when you milk them for father they must be washed, dried and absolutely free from loose dirt or hairs. I will always think that he was one of the cleanest milk producers ever. He really had the public interest at heart and he was not shy to tell us if his quick eye saw a dirty milking stool that may in turn dirty the hand that goes so near the milk.

Mother did the washing up with the help of a hired girl when available. I have memories of the kitchen floor being covered with tanks and cans all to wash, scald and dry, as was the practice in those days. At the same time, she would look after the dairy, make the beds and I never remember waiting for a meal when I came home from school or during all the years that followed. She was a marvel, always so bright, singing whilst working most of the time. Then in the comparative quiet of the afternoon, with only the dairy to look after, she would make out all the milk accounts, each in a small book (one for each individual customer).

My eldest brother Jack was very strong and it would be fair to say that he did most of the milking of the ‘hard’ cows. It always meant disappointment when one of the best cows had a teat trodden on, making it sore and hard to milk. That trouble must have cost the Liverpool farmer thousands of pounds in time and milk and sometimes loss of a cow, as inflammation was not so easy to conquer in those days without the penicillin and the antibiotics that we have today.

From 1874 onwards, nearby Sefton Park was our ‘farm’ for over fifty years. The men of Parks and Gardens would mow the grass 5½ days a week and we would rake it up and cart it away to the cows. We soon found out that one of the secrets of feeding grass to milk cattle is to feed it as soon after mowing as possible. We always found the cows gave less milk on Monday morning when we were feeding them grass that had been cut on Friday and Saturday; Father always arranged, with the co-operation of the park men, to mow the thickest grass on Friday afternoon and Saturday morning, to do us over the weekend. I always went to the park about 8:30 am on Monday morning in grass time and one of my most pleasant recollections is the memory of the sweet smell of the grass mown with the dew still on it. It must surely be one of nature’s very best. On Saturdays we always tried to get a very big load to have some reserves for Sunday. I had the job of loading the wagon and it had to be done so well that not one blade would fall off on the roads, which all had to be swept ‘lovely’ for Sunday. So, you can imagine the time that was spent, after the full load was on the wagon, raking down and pulling the loose bits off by hand to make absolutely sure none would fall on the park roads."

"I remember an alarming incident my brother and I experienced one morning with the horse and cart. We were going for grass near the Palm House. We drove down a steep path by the White Man and when we should have turned left up the bank to the field, the bearing rein had got caught on the right shaft so that the horse veered right where the was a three foot drop into the lake. As soon as the right wheel went over, the horse and cart and Jack and I had no alternative but to go with it. I assure you these lakes are very dirty at the bottom. I was falling backwards when Jack grabbed me by the chest so that I was able to walk out of the lake. He then proceeded to put the horse’s head on his knee and somehow managed to undo the shoulder chains and belly band so that the horse could fight his way free. As soon as he got to his feet the horse grazed away as though nothing had happened. I can still remember how I felt as I walked home to tell father the glad tidings. I can truly say that he was not amused.

This incident reminds me of another calamity. Jim, myself and Jack Armitt (a cousin of mine who used to come and help with the job when things were slack at the shipwrights) were coming back from Mossley Hill station with a load of coal. We were proceeding very nicely along Ullet Road, very near the junction of Sefton Park Road, and at this spot the road was made with rather too much crown. The poor horse slipped and down he went, breaking both shafts - and this was the show horse, Prince. After getting him to his feet we were very thankful to find he had no visible damage and just hoped he had not hurt himself internally or damaged his back. My brother Jack, getting a bright idea said “Aye Armitt. Go and tell me father and I’ll mind the load.” Armitt quite rightly replied “No. You go and tell him yourself. I’ll mind the load.” So, we borrowed a wagon from Jericho farm (my uncle was the tenant at that time), loaded the coal onto this and dragged the cart behind – taking it to be repaired later. It really was just one of those things that happened in those days. If we heard the cry “horse down” all the locals would drop everything and dash to the scene of this terrific drama!

I also had the job of carting the manure from the dairy farm. Father had a contract with the Liverpool Corporation to supply the parks in and around Liverpool. They just about took all the manure the cattle made, except for a few loads for the gentry’s house gardens and several allotments had their assured load too.

My boyhood memories are very happy ones. It is very true we worked hard but mother fed us extremely well. In between meals we went into the dairy where there was always a bowl of fresh milk and next to this was a large biscuit tin, half full of scones - somehow mother’s magic always produced homemade scones so we attacked these and drank lots of lovely creamy milk. In very hot weather we drank a lot of soda and milk, a very healthy drink that seems neglected nowadays.

We had three wonderful horses at home, Prince, May and Dick. Dick was the horse that I learned to ride on. When the horses were to be shod, we looked forward to the ride to and from the blacksmiths across the park in Mossley Hill. Both Prince and May had very successful show careers. The horse shows in those days were something very big. As many as forty horses in one class and the Liverpool May Day parade had to be seen to be believed. I am sure we witnessed the best collection of heavy horses in the world -- the Liverpool Corporation, the cartage companies at the docks and the brewers, all out to beat each other; this gave us, as horse lovers, the sight of a lifetime. Most of the biggest trophies had to be won three times before becoming the property of the exhibitor and both Prince and May were able to win outright these respective trophies. In my father’s retirement it was one of his great pleasures to show visitors his cups and silver plates won by his horses and cattle. You can imagine the pride I had riding either of these horses from the park and passing a number of my school friends. I was sure (rightly or wrongly) that they were green with envy!

When I was in my last year at school my father would go to Chester market on a Thursday to buy cattle, which would arrive at Lime Street station about four o’clock. I was given a note written by mother asking if I could be let out earlier to go and meet Father with the new cows, which was always a very big day in our life. Then we would drive them through Rodney Street, Windsor Street, Belvidere Road, Ullet Road and Parkfield Road, to the dairy. We would then all have a guess how much they were worth. I think this helped tremendously, as in later years when at a cattle market -- and remember, I went every week -- I could almost value each cow correctly to within 10 shillings. When I was asked to judge the cattle at the markets, prior to their sale, this was the method I adopted as I thought I would look a bit daft if the cow I had put second made £10 more than the one I had placed first. No matter how we try I suppose we all slip up now and again.

Showing the cows was another occasion that was very, very exciting for us all. As you know when you go to a show and you look at the cows in the ring, walking round so placid that you may think that they had been led on that halter all their lives. Don’t you believe it. First of all you find the cow that you think will be good enough to win. Then you proceed to get her home, say, four or five days prior to the show, and it’s only then that you put a halter on her and hope she will follow you like a dog. But, WOW! Most times she will put her head down and set off with four or five men in tow, as though they were paper dolls. If there was anything funny about it, it was the public’s reaction to a Home Town Rodeo. Ladies would pick up their skirts with the action of the best hacking horses, others would scream and knock at the nearest door begging to be admitted until the mad beast had passed. Sometimes they had just ventured back into the road when the cow decided a change of direction was the thing! But we always managed to tame the beast. And oh, how we enjoyed it -- the rougher the cow, the more the fun!

At home we always had a cowman and a girl, who lived-in with us. They were known as “sarvant man and sarvant lass”. Father would advertise for a man in the Liverpool Echo and sometimes we would have as many as forty after the job - mostly Irishmen, just off the boat. On one occasion we advertised for a girl to live-in and she arrived from Ireland. Bridget she said her name was and mother showed her to her room and bade her good night, after Bridget had assured mother she understood the gas. But about 1.30am the house was awakened with terrible moans from the direction of Bridget‘s room. Dad rushed in, opened the window and dragged Bridget out into the yard for air and then sent for the doctor, who ordered them to keep Bridget walking and drinking black coffee. After some time, she came round and the first thing she said was “take me back to the parish of Cragin and give notice to my mother that I’m dead!” That girl left the next day on the same boat that she came on and my bet is that she never came back.”

Thomas and his brothers worked for their father for very little pay — just pocket money. This was on the understanding that when the time was right, each would receive assistance from their father to set up their own dairy. Being the youngest in the family, Thomas had to wait his turn. But, in December 1937, he married Margaret Iris Owen (1905-1990) and with the assistance of Thomas’s father, the couple acquired a dairy at 48 ALWYN STREET, previously owned by John Herd. This property occupied a corner location; the dairy shop faced onto Alwyn Street and access to the back yard (where the cows were kept) was from Bryanston Road.

Life at Alwyn Street Dairy by Angela Hallows (nee Hogg)

“When my parents took over at Alwyn Street, in 1937, the milk round covered a wide area. As well as delivering locally in the St Michael’s area they stretched into Ullet Road and into Sefton Park. When war came, milk rounds were allocated by the Ministry to the vicinity of the dairy, so more efficient use of handcarts was introduced, replacing the horse and carts.

I was born in 1941 and my sister in 1942. The same cow men, George Lucas and John Kerr, stayed with us throughout my childhood. The third man, Harold Helsby, eventually left to run his own smallholding. The staff was completed by a large team of delivery boys who had to get the milk out by 8 o’clock – in time to get off to school.

My parents were two of the kindest people I have ever met. Dad seemed to draw people to him with their woes and would always help if he could. He had a great sense of humour and there was a great deal of laughter around."

I was born in 1941 and my sister in 1942. The same cow men, George Lucas and John Kerr, stayed with us throughout my childhood. The third man, Harold Helsby, eventually left to run his own smallholding. The staff was completed by a large team of delivery boys who had to get the milk out by 8 o’clock – in time to get off to school.

My parents were two of the kindest people I have ever met. Dad seemed to draw people to him with their woes and would always help if he could. He had a great sense of humour and there was a great deal of laughter around."

“From a young age I accompanied Dad to buy cattle at markets in Chester or Hellifield, or at farms throughout Lancashire, Yorkshire or Cheshire. There was constant movement between Alwyn Street and Jericho Farm. Hay making at Jericho was a highlight of the summer, as was the Annual Show At Liverpool Wavertree Playground. Dad had some success there and his trophies were always on display in the shop. Account books were delivered to customers each week and he made sure most were settled promptly by giving a penny bar of chocolate to every child who came in with a parent to pay.

Family ties in the Hogg family were strong, particularly with his brother Jack and his large family. He was also close to his cousins Eddie and Leslie. Family holidays were not possible because of the business, but every year, Dad, Eddie and Leslie went off together for a week in Douglas, Isle of Man. They also enjoyed short fishing trips to Yorkshire -- their roots in north Yorkshire were part of who they were."

Family ties in the Hogg family were strong, particularly with his brother Jack and his large family. He was also close to his cousins Eddie and Leslie. Family holidays were not possible because of the business, but every year, Dad, Eddie and Leslie went off together for a week in Douglas, Isle of Man. They also enjoyed short fishing trips to Yorkshire -- their roots in north Yorkshire were part of who they were."

Memories of Hogg’s Dairy

A number of people who grew up in that part of Aigburth have very fond childhood memories of Hogg’s Dairy in Alwyn Street.

Billy Williams and Glen Huntley used to work at the dairy:

Billy Williams: “I worked for Hogg’s Dairy when I was younger, delivering milk via their fleet of carts. We use to make a hell of a noise at 5:30am, loading up the carts with crates of milk then pushing them around the local streets.”

Glen Huntley: “Like Billy, I also worked for Hogg’s Dairy, pulling milk carts. I started at the age of 12 or 13 in the mid-1970s and my round was Chetwynd Street and Allington Street. It was really hard work, pulling a heavy 2-wheeled cart with 6 to 8 crates of milk on board in all weathers. One winter the snow was about a foot deep and I had customers come out and help me pull it. Christmas time was great as you got loads of tips when you took the holiday orders. One year I made £100 and that was the late 70s! That kept me in Airfix models and sweets for a while.

On really cold mornings we would stand in the fridge to keep warm; it sounds daft but the temperature was constant and so higher than outside. The scariest part of the round was pulling down Aigburth Road the wrong way.

I know Mr Hogg used to walk his cows along Bryanston Road to graze on the shore; I’m sure I remember the sound of bells in the morning as they passed our house. The pasture was on the other side of railway tracks, the entrance to which is the small patch of wild land that is still there, next to St Charles School in Tramway Road.”

Billy Williams and Glen Huntley used to work at the dairy:

Billy Williams: “I worked for Hogg’s Dairy when I was younger, delivering milk via their fleet of carts. We use to make a hell of a noise at 5:30am, loading up the carts with crates of milk then pushing them around the local streets.”

Glen Huntley: “Like Billy, I also worked for Hogg’s Dairy, pulling milk carts. I started at the age of 12 or 13 in the mid-1970s and my round was Chetwynd Street and Allington Street. It was really hard work, pulling a heavy 2-wheeled cart with 6 to 8 crates of milk on board in all weathers. One winter the snow was about a foot deep and I had customers come out and help me pull it. Christmas time was great as you got loads of tips when you took the holiday orders. One year I made £100 and that was the late 70s! That kept me in Airfix models and sweets for a while.

On really cold mornings we would stand in the fridge to keep warm; it sounds daft but the temperature was constant and so higher than outside. The scariest part of the round was pulling down Aigburth Road the wrong way.

I know Mr Hogg used to walk his cows along Bryanston Road to graze on the shore; I’m sure I remember the sound of bells in the morning as they passed our house. The pasture was on the other side of railway tracks, the entrance to which is the small patch of wild land that is still there, next to St Charles School in Tramway Road.”

Ann Robinson Ahlgren and Lynn Asbridge remember shopping at the dairy:

Ann Robinson Ahlgren: “As a little girl I lived on Rosslyn Street and passed two dairies on the way to school. One was Hogg’s Dairy. When I was old enough to carry a milk jug, I was sent for a pint of milk which was poured into my jug. This I carried home taking care not to spill any on the way. Going into Hogg’s Dairy was a very pleasant experience. It was cool and ultra clean. Sometimes there was a cloth to put on the top of the jug to keep the milk clean. We could look at the cows a little through a grid in the wall - and then we’d get the cow smell as well.”

Lynn Asbridge: “I lived in Errol Street. Tom and Margaret Hogg were very good to me. At lunch time, when I was in primary school at St Michaels, I would call at the dairy on Alwyn Street and Mr Hogg would give me a shopping list. It usually consisted of some sausages from Glendenning, choc ices for him and 20 Benson & Hedges for Mrs Hogg. At the end of the week, on a Saturday morning, I would call to see them and they would give me some pocket money. I was allowed to go into the yard to see the cows being milked and help sometimes. I would then fill bottles with cream and put the metal tops on by placing a metal cone over the lid and hitting it. I enjoyed every moment. They gave me gifts from faraway places such as a large piece of coral. They were very kind. I remember a large range in the kitchen with dinner cooking for the evening meal. I remember the cow which escaped and ran down Bryanston Rd. And also, John, the dairyman, who let me ride on his cart when he was delivering the milk. This was all between the late 60’s to early 70’s. Very fond memories.”

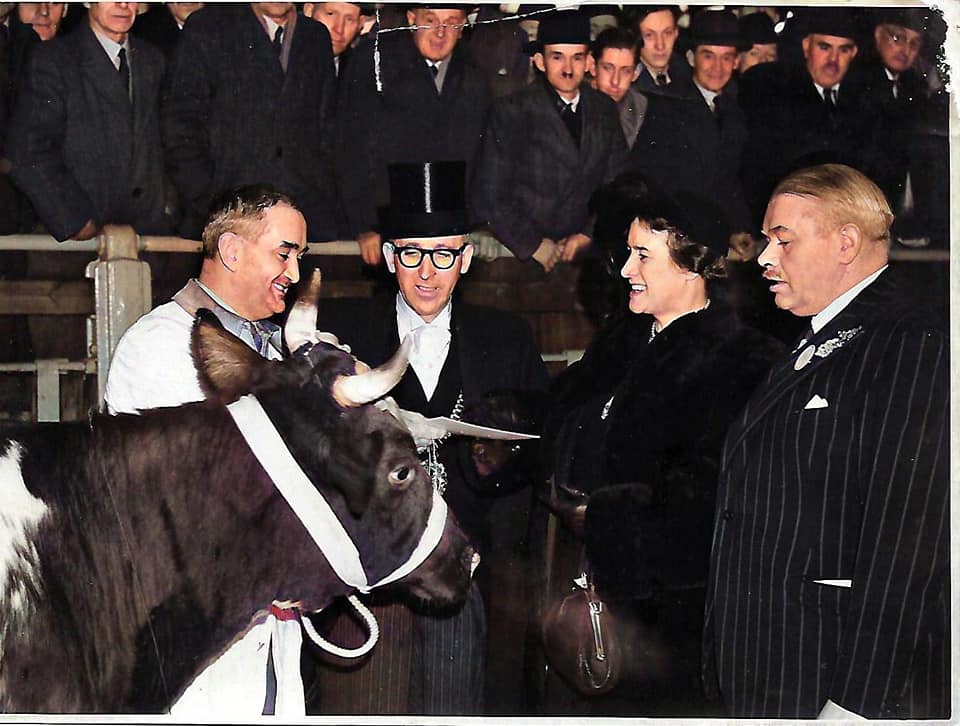

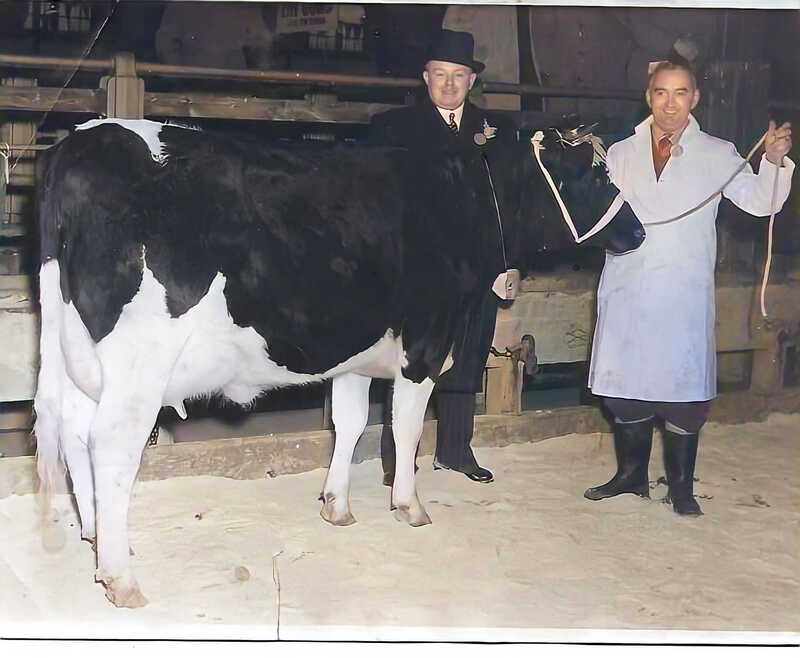

Showtime! – The Hogg’s prize-winning cows

Like most Liverpool cowkeepers, Thomas was a keen competitor at the local cattle shows, as had his father and grandfather been, before him. Major events included: the Christmas Show organised by the Liverpool Livestock Society (the successor of that previously organised by the Liverpool Cowkeepers Association); the Liverpool Show organised by the city council and held at Wavertree Playground; and also the Royal Lancashire Show, on those occasions when it was held in the city. Other, smaller shows, held in those parts of Lancashire adjacent to the city, were also attended, as they were within reasonable travelling distance. Not surprisingly, on more than one occasion, Thomas found himself competing against his father (John Hogg of Little Parkfield Road), his brother (also John Hogg of Little Parkfield Road!) or his cousin (James Leslie Hogg of Willowdale Road).

Archived newspapers give an indication of the success of the Hogg family at these events:

1938 - Christmas Show

Fat Cow (over 14½cwt.): 3. J Hogg, Little Parkfield Road.

Dairy Cow, calved (not over 10cwt.): 3. T Hogg, Alwyn Street.

1938 - Royal Lancashire Show

Fat cow, any weight. Highly Commended – John Hogg, 3 Back Parkfield Road.

1946 - Christmas Show

Fat Cows (exceeding 13½cwt.): 1. J L Hogg, Willowdale Road.

Dairy Cows, calved (exceeding 12cwt.) 1. J L Hogg; 2. J Hogg, Little Parkfield Road.

1947 - Christmas Show

Cow in calf, any weight: J L Hogg.

1949 - Christmas Show

Fat Cow (not exceeding 11½cwt.): 2. J L Hogg, Willowdale Road.

Cow, calved (not exceeding 11cwt.): 1. T L Hogg, Alwyn Street, Liverpool.

Cow, calved (not exceeding l0cwt.): 1. J L Hogg. Willowdale Road.

Cow, calved (exceeding 11cwt.): 3. T L Hogg.

Cow, calved (not exceeding 11cwt.): 2. T L Hogg.

1950 - Liverpool Show, (commenced 1949)

Dairy heifer, any breed, in calf or in milk. T L Hogg, Liverpool.

1950 - Christmas Show

Cow, calved (not exceeding 11cwt.): 2. J L Hogg, Willowdale Road.

Cow in calf, any weight: 1. T L Hogg, Alwyn Street.

Cow in calf or milk: 3. J L Hogg.

Cow or heifer in calf or milk, any weight: 2. J L Hogg.

1951 - Liverpool Show

Dairy cow, black and white, in milk. 1. J L Hogg, Liverpool.

Dairy cow, other than black and white, in calf. 1. T L Hogg, Aigburth, Liverpool.

Dairy cow other than black and white In milk under 10½cwt. 1. J L Hogg.

Pair of dairy cows or heifers, in calf or in milk (and winner of the Daily Dispatch Silver Challenge Trophy). 1. J L Hogg, with two first-prize winners.

Champion dairy cow or heifer in calf or in milk. Reserve and winner of the special prize presented by the North Shore Mill Co Ltd. – J L Hogg.

1951 - Christmas Show

Cow, calved (not exceeding 11cwt.): 1. J L Hogg.

1952 - Christmas Show

One of the most disappointed exhibitors was Mr J L Hogg of Walton, who had entered his British Friesian dairy cow, which won first prizes at Formby and Liverpool shows in 1951, but just before leaving for the show this morning, the cow calved and was unfit to be shown. Mr Hogg was only able to exhibit one of his dairy cows, a shorthorn.

Dairy Cow in calf or milk: 2. T Hogg.

Dairy Cow in milk (not exceeding 10½cwt.): 1. T Hogg.

Heifer in milk, not more than four broad teeth: 1. T Hogg.

Pair of dairy cows or Heifer in calf or milk: 1. T Hogg.

Championship Class – dairy cow or heifer in calf or milk: 1. T Hogg; 3. T Hogg.

Champion Cup for dairy cow or heifer in calf or milk: awarded to T Hogg.

Championship Cup for best shorthorn dairy cow in milk: awarded to T Hogg.

Championship Cup for best dairy cow (not exceeding 10½cwt.): awarded to T Hogg.

1953 Christmas Show – no more classes for dairy cows

1953 - Liverpool Show

Dairy cow in milk – J L Hogg, Liverpool.

Dairy heifer in calf or milk – T L Hogg.

Champion dairy cow or heifer – J L Hogg, Liverpool.

Two-wheel Tradesman’s Turnout – John Hogg, Liverpool.

1956 - Liverpool Show

Dairy cow in milk – T L Hogg.

Pair of dairy cows or heifers in calf or milk – T L Hogg.

city milk — From Cow to Customer

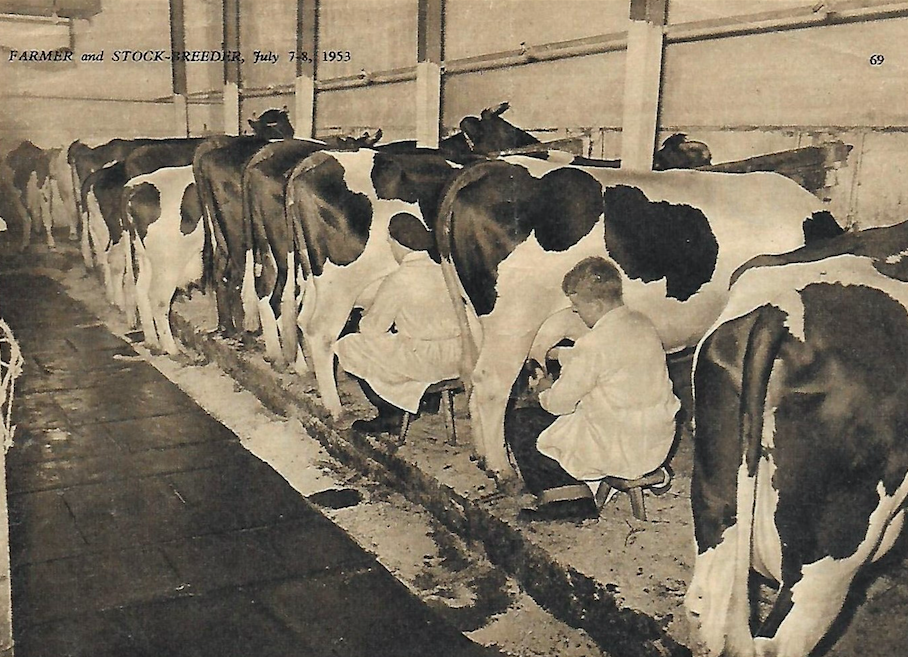

This is a transcript of an article that appeared in Farmer and Stock-breeder magazine, July 7-8 1953 (page 69). It not only describes Thomas’s operation at Alwyn Street but also provides a fascinating insight as to the state of the town dairy industry at that time. Sadly, the ‘sounder footing’ that Tom was hoping for, never came to be.

FROM COW TO CUSTOMER IN LIVERPOOL

The town dairymen of this great city have dwindled but there are still 30 who carry on

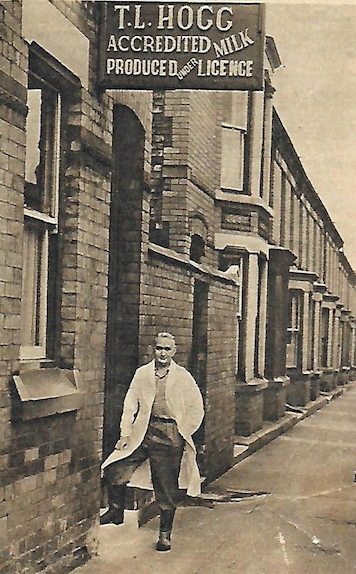

In the last 12 months Mr T L Hogg produced in the city of Liverpool 54,000 gallons of milk, as well as 800 tons of muck for export to the arable farmers of Lancashire, from his herd of cows kept at Alwyn Street, Aigburth. He is one of the remaining members of the old Liverpool Cowkeepers’ Association, and his premises are in the heart of a densely populated area of houses and shops.

Mr Hogg’s herd is one of the 30 left in Liverpool, surrounded by clanging trams and with cobbled streets in place of pastures. He is a producer-retailer and has 4,000 customers within a radius of half-a-mile. He milks at 5am and his deliveries are all made by 9am.

Such establishments may be thought something of an anachronism these days but the Alwyn Street business is flourishing despite the high cost of feeding stuffs, which have all to be bought in. With the freeing of feeding stuffs from control and development in T.T. production and pasteurisation, Mr Hogg is hopeful that enterprises such as his will be placed on an even sounder footing.

FROM COW TO CUSTOMER IN LIVERPOOL

The town dairymen of this great city have dwindled but there are still 30 who carry on

In the last 12 months Mr T L Hogg produced in the city of Liverpool 54,000 gallons of milk, as well as 800 tons of muck for export to the arable farmers of Lancashire, from his herd of cows kept at Alwyn Street, Aigburth. He is one of the remaining members of the old Liverpool Cowkeepers’ Association, and his premises are in the heart of a densely populated area of houses and shops.

Mr Hogg’s herd is one of the 30 left in Liverpool, surrounded by clanging trams and with cobbled streets in place of pastures. He is a producer-retailer and has 4,000 customers within a radius of half-a-mile. He milks at 5am and his deliveries are all made by 9am.

Such establishments may be thought something of an anachronism these days but the Alwyn Street business is flourishing despite the high cost of feeding stuffs, which have all to be bought in. With the freeing of feeding stuffs from control and development in T.T. production and pasteurisation, Mr Hogg is hopeful that enterprises such as his will be placed on an even sounder footing.

Mr T. L. Hogg keeps his dairy herd in a densely populated part of Liverpool and has many satisfied customers.

Mr T. L. Hogg keeps his dairy herd in a densely populated part of Liverpool and has many satisfied customers.

A Century Ago

The old Liverpool Cowkeepers’ Association has been re-born under the name of Dairy Farmers’ Creamery (Liverpool) Ltd. Dairy farming in Liverpool became an industry a century ago, when the city was rapidly expanding and its geographical bottleneck situation was a handicap in bringing in sufficient milk to supply the rapidly growing number of homes.

So dairy farms were started in the city itself, and they remain even when the tide of expansion caused an ocean of bricks and mortar to flow around them. As recently as 1939 there were more than 100 Liverpool cowkeepers. The city’s health department laid down stringent rules of cleanliness and hygiene, which were loyally observed.

Many of the old cowkeepers lost their farms in the blitzes; others perished in the economic stress of the war years. But there are still 30 and one in Raffles Street has a Liverpool 1 address, with departmental stores as its neighbours.

Delayed by the War

The Liverpool cowkeepers have progressed with the times, and they have just reached the end of the first year’s running of their own pasteurisation and distribution centre. Realising that pasteurisation was necessary they made plans early, but they were delayed by the war.

Most of the cowkeepers invested capital in the new venture, in amounts ranging from £500 to £2,000, and at the end of 1951 a modern dairy was set up in a factory in Kirkby. The factory alterations and the plant cost £70,000, which meant substantial help from the banks to support the individual investments.

In just over a year of operation the dairy has quadrupled, to 4,000 gallons a day, the amount of milk it handles. There is a staff of 23. Within another year, it is hoped, it will be possible to pay bonuses to the cowkeepers and dividends to investors.

In common with his fellow town dairymen, Mr Hogg has an eye for a good milk beast. He favours the British Friesian and has 28 milking. Previously he bought cows round about their third calving, but is now finding that heifers can be found that produce well from the start and can be kept for several years. His cows are artificially inseminated with the semen of a Hereford and there is a good market for the calves.

The little community of Liverpool cowkeepers has high standards; its members are proud of their long tradition as producer-retailers, dealing in milk from cow to customer in the heart of a great city.

Interestingly, key operational statistics for the Alwyn Street dairy that can be extrapolated from the article are as follows:

The old Liverpool Cowkeepers’ Association has been re-born under the name of Dairy Farmers’ Creamery (Liverpool) Ltd. Dairy farming in Liverpool became an industry a century ago, when the city was rapidly expanding and its geographical bottleneck situation was a handicap in bringing in sufficient milk to supply the rapidly growing number of homes.

So dairy farms were started in the city itself, and they remain even when the tide of expansion caused an ocean of bricks and mortar to flow around them. As recently as 1939 there were more than 100 Liverpool cowkeepers. The city’s health department laid down stringent rules of cleanliness and hygiene, which were loyally observed.

Many of the old cowkeepers lost their farms in the blitzes; others perished in the economic stress of the war years. But there are still 30 and one in Raffles Street has a Liverpool 1 address, with departmental stores as its neighbours.

Delayed by the War

The Liverpool cowkeepers have progressed with the times, and they have just reached the end of the first year’s running of their own pasteurisation and distribution centre. Realising that pasteurisation was necessary they made plans early, but they were delayed by the war.

Most of the cowkeepers invested capital in the new venture, in amounts ranging from £500 to £2,000, and at the end of 1951 a modern dairy was set up in a factory in Kirkby. The factory alterations and the plant cost £70,000, which meant substantial help from the banks to support the individual investments.

In just over a year of operation the dairy has quadrupled, to 4,000 gallons a day, the amount of milk it handles. There is a staff of 23. Within another year, it is hoped, it will be possible to pay bonuses to the cowkeepers and dividends to investors.

In common with his fellow town dairymen, Mr Hogg has an eye for a good milk beast. He favours the British Friesian and has 28 milking. Previously he bought cows round about their third calving, but is now finding that heifers can be found that produce well from the start and can be kept for several years. His cows are artificially inseminated with the semen of a Hereford and there is a good market for the calves.

The little community of Liverpool cowkeepers has high standards; its members are proud of their long tradition as producer-retailers, dealing in milk from cow to customer in the heart of a great city.

Interestingly, key operational statistics for the Alwyn Street dairy that can be extrapolated from the article are as follows:

- 4,000 customers within half-a-mile of the dairy.

- 28 cows producing 54,000 gallons of milk per year.

- Each cow producing an average 5.3 gallons of milk per day.

- 28 cows producing 800 tons of muck per year.

- Each cow producing an average 28.6 tons of muck per year.

Man of the Week!

This second article is taken from an unidentified and undated local newspaper. It looks like there was a regular feature profiling a local personality. In the issue in question, that local personality was 58-year-old Tom Hogg (suggesting the article was published in 1952/3). As in the first article, Tom remains optimistic about the future of town dairying, ‘hanging on’ for better times.

Man of the Week – Mr Thomas L Hogg

In a tidy street of terraced houses in the heart of Liverpool a man is keeping a herd of 24 dairy cows — and everybody is happy about the idea, including the city’s health authorities.

The man is Mr Thomas L. Hogg — and his neighbours within a half-mile radius, are his customers. Each morning something like 75 per cent of them have their morning milk on the doorstep by eight — delivered by Mr Hogg’s team of eight lads.

Mr Hogg is one of the city’s three remaining traditional cowkeepers. He feeds his Friesian herd on wet grain, molasses and biscuit waste from a factory on the outskirts of the city. And he makes sure they get plenty of common salt, which they need, he says, to keep in good health.

Mr Hogg sells between 170 and 180 gallons a day – 140 when the two schools he serves are closed for holidays. He sells his calves at two or three days old, and the last one he sold, two or three weeks ago, fetched £20.

Not that 58-year-old Mr Hogg is happy about the milk business. In fact he admits he is “hanging on” for the better times he thinks must come. He is one of eight directors of a creamery on the outskirts of the city, which was started just after the war and now handles up to 9,000 gallons a day.

He is also chief steward of the Liverpool Show, a task he obviously enjoys because it gives the folk of the city a chance to take a look at country interests.

“I enjoy my job and I enjoy my life,” he says. He likes motoring, fishing in the Yorkshire Dales — “I like the places it takes me to” — and an occasional game of golf.

He has two daughters, one a secretary in New York. And Mr Hogg, the town farmer of Liverpool’s Alwyn Street, has another interest. Every year he composes the verse for the Christmas card sent out by the Lancashire Federation of Young Farmers. It is a message that mingles in rhyme, some of the sentiments of the season, with a sharp assessment of the current farming scene. One feels that this too, is a task he enjoys immensely.

Tom’s hopes that things would improve for town dairies like his, were ultimately frustrated. But the dairy at Alwyn Street saw him through until he was ready for retirement. In 1969 it was taken over by two of Tom’s nephews, Jack and Norman Hogg (the two eldest sons of Jack and Annie Hogg).

Man of the Week – Mr Thomas L Hogg

In a tidy street of terraced houses in the heart of Liverpool a man is keeping a herd of 24 dairy cows — and everybody is happy about the idea, including the city’s health authorities.

The man is Mr Thomas L. Hogg — and his neighbours within a half-mile radius, are his customers. Each morning something like 75 per cent of them have their morning milk on the doorstep by eight — delivered by Mr Hogg’s team of eight lads.

Mr Hogg is one of the city’s three remaining traditional cowkeepers. He feeds his Friesian herd on wet grain, molasses and biscuit waste from a factory on the outskirts of the city. And he makes sure they get plenty of common salt, which they need, he says, to keep in good health.

Mr Hogg sells between 170 and 180 gallons a day – 140 when the two schools he serves are closed for holidays. He sells his calves at two or three days old, and the last one he sold, two or three weeks ago, fetched £20.

Not that 58-year-old Mr Hogg is happy about the milk business. In fact he admits he is “hanging on” for the better times he thinks must come. He is one of eight directors of a creamery on the outskirts of the city, which was started just after the war and now handles up to 9,000 gallons a day.

He is also chief steward of the Liverpool Show, a task he obviously enjoys because it gives the folk of the city a chance to take a look at country interests.

“I enjoy my job and I enjoy my life,” he says. He likes motoring, fishing in the Yorkshire Dales — “I like the places it takes me to” — and an occasional game of golf.

He has two daughters, one a secretary in New York. And Mr Hogg, the town farmer of Liverpool’s Alwyn Street, has another interest. Every year he composes the verse for the Christmas card sent out by the Lancashire Federation of Young Farmers. It is a message that mingles in rhyme, some of the sentiments of the season, with a sharp assessment of the current farming scene. One feels that this too, is a task he enjoys immensely.

Tom’s hopes that things would improve for town dairies like his, were ultimately frustrated. But the dairy at Alwyn Street saw him through until he was ready for retirement. In 1969 it was taken over by two of Tom’s nephews, Jack and Norman Hogg (the two eldest sons of Jack and Annie Hogg).

‘Tomog’ the Poet

Tom’s talent for rhyme, as described in the Man of the Week newspaper article, is evident in the following two poems, composed under his self-styled moniker of ‘Tomog’. The first poem expresses his passion for the place that was the cradle of the Hogg family, the Yorkshire Dales. The second demonstrates his sense of humour as he provides a cow’s perspective on artificial insemination!

Yorkshire Dales

I am able to relax here

Where everything is still

‘Cept the rustle of the heather

The trickling water in the gill.

The calling of the curlew

The bleating of a lamb

My mind reads “let me stay here

In this heaven where I am”.

I have wandered over Scotland

Seen the rugged beauty that is Wales

But my mind finds such contentment

In these lovely Yorkshire Dales.

Maybe it’s the cooking - the folk serve a tasty dish

Then perhaps it is the rivers - where in peace I oft times fish.

I only know I have a yearning

No not for foreign shores

But to see nature in ALL her moods

On the lovely Yorkshire moors

Artificial Insemination!

I have just given birth to a calf Sir

And of motherly pride I am full,

But please do not laugh and please do not chaff

When I tell you I’ve not met a bull.

The farmyard’s the dreariest place now

And the meadow not even so gay,

When the one bit of fun in the year’s dismal run

Has by science been taken away.

What I think maybe quite out of place Sir

There are things that we cows should not say,

For these Land Army tarts who play with our parts

Still have it the old-fashioned way.

Tomog

Yorkshire Dales

I am able to relax here

Where everything is still

‘Cept the rustle of the heather

The trickling water in the gill.

The calling of the curlew

The bleating of a lamb

My mind reads “let me stay here

In this heaven where I am”.

I have wandered over Scotland

Seen the rugged beauty that is Wales

But my mind finds such contentment

In these lovely Yorkshire Dales.

Maybe it’s the cooking - the folk serve a tasty dish

Then perhaps it is the rivers - where in peace I oft times fish.

I only know I have a yearning

No not for foreign shores

But to see nature in ALL her moods

On the lovely Yorkshire moors

Artificial Insemination!

I have just given birth to a calf Sir

And of motherly pride I am full,

But please do not laugh and please do not chaff

When I tell you I’ve not met a bull.

The farmyard’s the dreariest place now

And the meadow not even so gay,

When the one bit of fun in the year’s dismal run

Has by science been taken away.

What I think maybe quite out of place Sir

There are things that we cows should not say,

For these Land Army tarts who play with our parts

Still have it the old-fashioned way.

Tomog